Dreaming of a Regulatory Regime

Cryptocurrency regulation in the United States causes some to doubt the industry's future. There has to be some path forward, but what should it be?

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with legal questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

Much news this week as Kalshi continues to wage its legal battle with the CFTC. On Thursday, the two sides sparred before a panel of three Democratic appointees in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. We will likely know soon whether the CFTC will be awarded a stay pending appeal, effectively keeping Kalshi’s elections based event contracts off the market for the duration of the 2024 election cycle. To my ear, the judges sounded skeptical of Kalshi’s core reading of the CEA, but other observers disagreed, and we won’t know until the court tells us.

Elsewhere in Washington, the SEC settled charges with Rari Capital, Inc. for unregistered broker activity and unregistered securities offerings. Rari made no admissions in the settlement, and so the SEC’s claims will forever remain “allegations”, but they amounted to Rari offering the public various flavors of unregistered “earn pool tokens” that would pay yield based on the profits earned by investment pools pool. The SEC also alleged that governance tokens sold by Rari were unregistered securities offerings, which maybe would have been more difficult for them to prove up in court had they gotten there.

This is a fairly typical SEC enforcement action these days, and it got me thinking about conversations I’ve had about regulation coming into the industry. It’s common among professionals to wonder when new regulation will enter the industry and what it might be, but I rarely hear my colleagues discussing what that regulation should be. This week I’m asking the question. Is there a gating regulatory issue that if it were solved could unlock the industry? What prescriptive rules should be put in place for the industry to flourish?

Why has crypto been so successful?

When thinking about the high value achieved by cryptocurrency projects over the years, one model is that this is regulatory arbitrage. The technology obviously has some novel and useful applications, like decentralized transaction validation and immutable recording of those transactions, but much of the value from these tools comes from what those properties allow you to do. The simplest account of that value is that blockchain allows you to reach new markets, but the reason these markets are accessible is because they were previously cut off from traditional financial products by regulation.

Of course, these regulations are multifarious. Part of the beauty of the halcyon days of crypto was that it ignored all of it. Cloaked in perceived anonymity it dared to be permissionless, neither gating participant permission or asking for permission to exist. I’ve written here about a half dozen regulators who have pushed that initial wave back, and there are more.

Nearly every crypto use case is evading some scheme meant to systematize or supress some kind of economic activity. For example, why are cross-border remittances the paradigmatic use case for cryptocurrencies? Because governments across the world prohibit or tax these transactions.

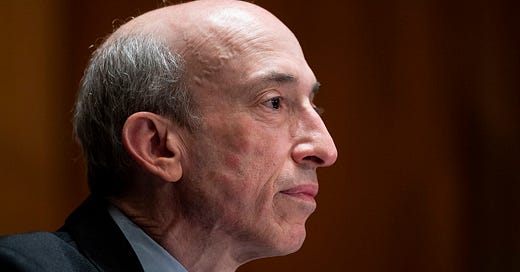

I only want to focus on securities regulations this week, though. This is for a couple reasons. For one, the token is the essential quantum of the crypto economy. Secondly, SEC enforcement of securities laws has effectively limited the ability of projects to launch new tokens and gain traction. We’ve mentioned this here before, but a large majority of the most valuable crypto projects were launched before Gary Gensler first took power in 2021. In 2024, it is very difficult to raise funds through a token launch in the United States. In the future, I contend, it shouldn’t be.

Why does crypto need new regulation?

It should be clear now that U.S. crypto projects will not be able to evade securities law through anonymity or decentralization. If the SEC chooses to continue its emphasis on cryptocurrency projects, it will likely thus be able to prohibit new token launches. This eventuality is obviously not good for the sector, but it can be credibly argued that it is not good for the United States either. It will drive these projects abroad, where their benefits will redound to different people. Elizabeth Warren may believe that crypto does more harm than good, but I don’t. So what should the regulatory regime actually be?

To credibly answer this question, we must first answer another — how are securities laws as they exist now broken? After all, if these laws were perfectly calibrated then transgressing them would only harm society. It is only by understanding how transgressive applications overcome the failures of a schlerotic regulation that we can arrive to an compelling argument for crypto’s net benefit to society. We have to think there is something wrong to begin with.

Then we can parlay this understanding. After all, a desirable new regulatory scheme will acknowledge the good that some transgressive application brought into the system, and then integrate it moving forward.

Uber is the perfect example of this. Previously, taxicabs were operated through a highly regulated monopoly of medallion holders. This created limited supply, drove up prices (arguably), and imposed perverse incentives to innovation. Uber operated outside of this scheme, illegally (arguably), and exposed the benefits of a transgressive rideshare system. Now, it is legal in most places, and we are largely better for it. The transgression was a phase on its path to affirmative legality. Crypto is at a juncture where it must do the same thing, or else wither.

Securities regulation in the United States.

Federal securities laws were initially implemented through, and still is largely based on, a series of legislation from the 1930s and 40s. Passed during the Great Depression, the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Investment Company Act of 1940 created a regulatory regime meant to combat fraud and malfeasance in the investment industry and restore faith in investing. Together they require registration of publicly traded securities, of exchanges, and of broker-dealers; create disclosure requirements for securities; and empower the SEC to prosecute inaccuracies in those disclosures as fraud. Some argue that this regime has been successful and “enforcement intensity gives the U.S. economy a lower cost of capital and higher securities valuations.“

Whether or not the regime is the cause of the success of U.S. securities markets in the intervening 90 years, it clearly did not prevent success, as the S&P 500 has experienced a mind melting 1,905,241.52% increase since 1933. On some level, securities laws work.

And yet, there are clear tradeoffs. For one, registration and disclosure requirements impose large costs on public markets. The accounting firm PricewaterhouseCooper (PwC) estimates that the average cost of a public offering is $9.5-$13.1 million. Similarly, public company compliance costs from annual and quarterly disclosures and Sarbanes-Oxley statements are generally around the same order of magnitude. Even the SEC has recognized that “disclosure requirements place a disproportionate burden on smaller reporting companies in terms of the cost of, and time spent on, compliance.”

Beyond just these direct costs, there is also a constant fear of securities fraud, as some commentators believe that courts have taken the view that “everything is securities fraud” and virtually any omission on a quarterly filing could lead to a successful lawsuit against a public company, further increasing costs of operating within the regime.

Together, these impediments make it prohibitively difficult for small new entities to access public capital markets in the United States. While a hawkish securities regulator may view this as a good thing, it is a fundamental restriction on liberty not just to these projects but also to the public at large, which appears highly interested in investing in private markets. This is evidenced by the extreme premiums at which exchange traded funds (ETFs) containing shares of private companies trade.

But aren’t there other ways to raise money?

While there are a number of exceptions like Regulation A, Regulation D, and Regulation CF that allow small entities to raise money through public markets with less onerous compliance, these each come with their own restrictions. Most importantly, they substantially limit secondary market liquidity for shares sold in one of these offerings by imposing lockups and resale restrictions. This means that while successful projects may be able to raise funds through one of these exceptions, insiders and investors may still struggle to trade their own ownership stakes, and the public will still find it difficult to get exposure to the upside of novel private firms.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

By creating facially plausible arguments for the non-applicability of securities laws (or non-enforceability), crypto short circuited this entire system. For a time, the industry operated with a funding model, that allowed exciting new projects to raise public funds without onerous compliance costs. At the same time, the cryptocurrency tokens created by this model were treated as completely liquid on the secondary market, allowing innovators and investors to quickly realize returns on their successes. The public was generally completely free to gain as much exposure to the upside of the industry as they wanted, and many became quite wealthy purchasing and trading cryptocurrencies.

But, as discussed, those regulations were there for a reason, and crypto experienced the gamut of problems that one would expect to occur in an unregulated securities market. Without systematized requirements for public disclosures prior to launch, there have been endless pump and dump scams — as much as 24% of all tokens according to blockchain firm Chainalysis. Speculative token projects like Terra Luna gained substantial following and collapsed spectacularly. Unburdened by the strict compliance obligations of a securities exchange, the crypto exchange FTX invested demand deposits in venture bets, embezzled customer assets to purchase real estate, and generally had a “complete failure of corporate controls [and] complete absence of trustworthy financial information.” Then it collapsed.

Enforcement agencies have taken this as proof of their necessity, but it cuts both ways. Enforcement may reduce the incidence of catastrophic collapse harming public shareholders, but it does so at a substantial cost. In any case, SEC oversight doesn’t prevent this kind of problem, as should be clear from well known public failures like Enron and Lehman Brothers. Some costs are accepted in exchange for some benefits. The promise of crypto is to create a parallel market with divergent risk benefit calculus.

So what is the right system?

A new securities regime in cryptocurrency should create a path to legal offer and trading of cryptocurrency tokens. It should provide clear guidance to intermediaries, banks and vendors of crypto projects that allow them to operate without unecessary regulatory risk and uncertainty. It should do all of this in the interest of creating vital, high risk, capital markets to allow public funding of (and thus exposure to) novel products and ideas.

These public markets, and especially secondary market liquidity, are valuable even in light of the increased risk they engender, not as a replacement to traditional public capital markets, but as a parallel system.

This means creating a path for unregistered offering of cryptocurrency tokens to public investors in the United States. Of course, these offerings should not be permitted to make untruthful or false public representations about the tokens and underlying project they support, but the cost of truthful marketing is markedly less than the tens of millions of dollars that public market compliance currently demands.

Beyond truthfullness, these markets should have other limitations as well. Particularly, cryptocurrency tokens should not be able to free ride on the imprimatur associated with public equity shares regulated through traditional security markets.

It is likely that securities regulation in the United States has supported the value of equities, the financing of projects, and thus the growth of the economy as a whole by creating very stable and trustworthy markets. It is also likely that part of the value of cryptocurrency came from emulating these markets without the attendant compliance costs and access restrictions.

This harms the traditional markets by undermining their reputations when crypto markets turn out to instead be volatile and risky. For this reason, a path to legitimacy for cryptocurrency tokens may involve deliberate labeling to identify the increased risk of this kind of asset. Arguably, this could be supported by requirement that crypto tokens do not trade side by side with regulated securities, and possibly not on the same platform or through the same application. Ultimately, the risk is the point for public investors. This is what gives exposure to higher upside, and probably an increased risk premium, but nobody benefits from retail investors being misled as to the extent of this risk.

Direct P2P trading of cryptocurrency tokens does not require special regulation. Of course, these trades should be subject to private rights of action under theories of e.g. common law fraud or breach of contract, they likely do not need an executive agency specifically monitoring them to be (relatively) safe and efficient. The same is probably true of trading on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) that effectively match buyers and sellers without centrally custodying cryptocurrency assets. There are obviously substantial risks of using these tools to trade in cryptocurrencies, but retail consumers should be able to evaluate these risks and weigh the benefits relative to the costs that may be associated with trading through central intermediaries.

Those central exchanges, on the other hand, should be highly regulated. While the ideal regime need not mirror that of a traditional securities exchange, there is no benefit to anyone of a centralized intermediary operating like FTX. Indeed, the systemic risk of runnable assets being custodied by a central intermediary without reserve requirements, concentration requirements, liquidity requirements, etc. is substantial. Unregulated banks and exchanges of cryptocurrencies have none of the fundamental benefits of the underlying cryptocurrency capital markets themselves. They should be regulated just as strictly as custodians of any other asset class.

They should, however, find a path to legitimacy. The SEC has in recent years brought action against entities like Coinbase for facilitating securities transactions. Instead it should offer clear operational standards. By actually regulating, instead of attempting to enforce a hamfisted prohibition, the SEC could improve confidence in crypto intermediaries while protecting users from bad actors. If the SEC instead focuses on the core activity, transacting in cryptocurrency assets, the public will have no way to distinguish between custodians with very different practices on the “backend.” These practices are incredibly important to the risk that consumers will ultimately be exposed to, but they are difficult to ascertain on an individual basis, which makes them an appropriate locus for regulation.

Evaluating this proposed regime, one might wonder what will keep it in “parallel” to traditional capital markets. After all, without the high compliance costs of traditional equities, why wouldn’t companies choose to offer new equity in the form of cryptocurrency. A regime could address this, for instance by placing cryptocurrency tokens lower on the “bankruptcy waterfall”[1], however it might not need to. Companies have choices now in the form of fundraising they choose, and this could be the same under this regime. While now a company might issue new equity or a bond to raise capital, in the future it might choose a cryptocurrency token when investors were interested in a volatile, highly liquid asset. On the other hand, many investors will still likely prefer the relative safety of a well regulated equity security. It is possible that cryptocurrency tokens could outperform traditional equity securities so completely that they were driven to obsolescence, but unlikely.

And so cryptocurrency could become a new class of financial asset. This permissive structure could provide the minimum protections necessary to prevent consumer injury, while generally relaxing onerous compliance and democratizing access.

Of course, this regime leaves unanswered many relevant questions about the status of other cryptocurrency fundamentals like stablecoins and decentralized finance (DeFi). Those areas are important, but may fall more neatly under non-securities regimes, and so we will have to discuss them on another day. Until next time.

[1] When companies enter bankruptcy, creditors are paid in a prescribed order based on the seniority of their credit. Traditionally, equity is paid last. In general, this means equity is not paid at all in bankruptcy, though sometimes there are scraps left over.

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.