A Broader Perspective on the Tether News

The United States Department of Justice is reportedly investigating Tether, and that may be just the beginning.

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with legal questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

We’re Having a Party!

Welcome back to another week of the Brogan Law Newsletter! Before we get into the analysis this week, a personal note. Brogan Law is co-hosting an event on Nov. 6 with our friends at NAXO and Department of XYZ. Many of you dear readers will already be in attendance, but there remain a few spaces open for industry participants. I consider NAXO and Dept. of XYZ both to be the elite in their respective fields, and getting to spend time with them is a prize in itself. This event will also be a great opportunity to meet members of the blockchain business community in New York, hear some thoughts on the next four years of regulation from myself and the other hosts, and enjoy some excellent food and drink. If you are interested, you can register here at: https://lu.ma/tx707zxd. Feel free to invite other members of the community in New York, or your partners, as well. Because of limited space, I cannot guarantee that everyone who registers will be able to attend, but I would love to have you all—now on to the newsletter.

The DOJ Investigation of Tether

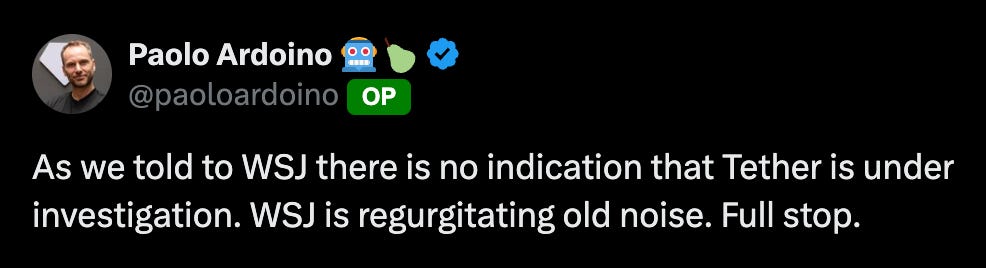

The Wall Street Journal broke the news this week that the United States Department of Justice (“DOJ”) is investigating Tether for potential sanctions violations. This reporting is dire for the company, particularly in concert with the revelations that the United States Department of Treasury (the “Treasury”) is considering sanctioning Tether itself.

The Treasury Department, meanwhile, has been considering sanctioning Tether because of its cryptocurrency’s widespread use by individuals and groups sanctioned by the U.S., including the terrorist group Hamas and Russian arms dealers. Sanctions against Tether would generally prohibit Americans from doing business with the company.

This news should be alarming both to Tether and to the cryptocurrency industry as a whole. Sanctioned status would be a near-death sentence for Tether (at least in Western countries), and the precedent such harsh punishment would set for other stablecoin issuers could dramatically increase compliance costs around the industry.1

According to CoinMarketCap, Tether’s stablecoin, USDT, depegged by twenty-five ten-thousands of a cent ($.0025) Friday, and as of publication it is still trading near its lowest price this year.

Regulatory Status of Stablecoins

By now, readers of this newsletter will be very familiar with crypto’s most prominent regulatory issues: securities law and CFTC futures and derivatives law. Tether, USDT, and stablecoins at large generally implicate neither of these regimes. While Tether was the subject of a CFTC investigation and $41 million fine in 2019, this was related to its status as a commodity, not as a swap or future.

Stablecoins like USDT are intended to hold a “peg” and maintain a consistent value relative to some other asset, like one unit of a currency like USD. There are generally two approaches to this, one is algorithmic, favored by certain firms like MakerDAO, which use algorithms to strategically buy and sell tokens to manipulate supply, thereby maintaining a certain value.

The second method is pegging by collateralization. In the purest version of this model, a stablecoin issuer accepts one unit of collateral in exchange for one stablecoin and then agrees to exchange the stablecoin back for a unit of collateral freely. In this way, the value of the stablecoin should closely approximate that of the unit of collateral it can be exchanged for—perhaps less an amount of transaction fees and residual risk.

The problem with this collateral model is that holding lots of dollars in the form of dollars costs money and doesn’t earn any income. To accommodate this, issuers adopted a model of maintaining mixed pools of collateral, mostly in the form of highly rated and predictable liquid assets like Treasury Bills, roughly the same way that retail banks do. This earns them an income, and is mostly fine.2

Where Tether went wrong between 2014 and 2019 (according to the CFTC) was in saying that USDT was backed “1:1” by fiat reserves, but in fact backing USDT with a mix of other assets in reserve. The CFTC described this practice as “misleading.” In addition, the CFTC identified certain audit failures, and the amount of fine imposed was, ultimately, quite significant (compare the $41 million Tether fine to the $175,000 Uniswap fine we covered a few weeks ago). Nevertheless, Tether has since operated in a state of quasi-legality, and practitioners have looked the case to identify compliance guardrails for other stablecoin issuers.

Tether’s issues now are different, and in some ways even more serious.

OFAC Sanctions

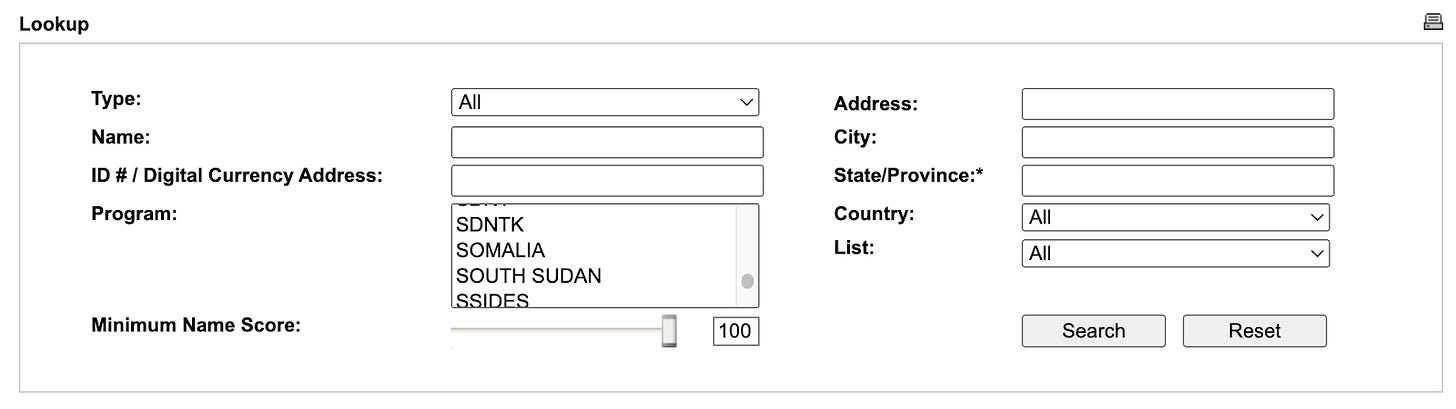

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) sits within the Treasury and has broad authority to implement and enforce United States sanctions law globally. This authority first originated from the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, which empowered the President to seize and control foreign assets, a power since delegated to the Treasury. President Harry Truman then created OFAC in 1950 to administer these responsibilities (and to block Chinese and North Korean assets). Since then, new sanctions powers are added by legislation from time to time, most notably the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 which empowered the President to issue executive orders blocking assets. Legislation can also create bespoke sanctions programs, and the net of all of this is a very complex web of sanctions spanning the globe. This mess is managed by OFAC as a series of lists, such as the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list ("SDN List").

The effect of being included on one of these lists or being “blocked” is generally a blanket prohibition on trade with US persons, a ban from accessing the US financial system, and a freeze of all assets held in the United States. OFAC also imposes “secondary sanctions” on entities that are known to trade with directly sanctioned persons and entities, meaning those parties can also be blocked. This, effectively, enforces US sanctions globally, or at least in the parts of the globe that are closely affiliated with the United States.3

These regimes have become powerful international policy tools for the United States, but the United States lacks jurisdictional reach to enforce them directly against their targets. Instead, the laws themselves must be enforced against US Persons.4 If you’re going to prohibit trade with North Korea, you can’t regulate North Korea itself—you regulate your own people.

These regulations are viewed as incredibly strategically important to the United States’ national security (“NatSec”) regime, and they can only be effective if strictly enforced. Preventing half of US Persons from trading with Iran makes goods more expensive, preventing all US Persons from trading with Iran cripples Iran. For this reason, sanctions violations penalties are severe, including asset seizure and forfeiture, large monetary penalties, felony criminal penalties, and, for entities, secondary sanctions which are, in effect, the death penalty.

Moreover, to make these regimes easier to enforce, they include no mens rea or intent component. Generally, to be convicted of a crime, one must have a “mens rea” or guilty mind. While there are different standards, this is protective of persons by requiring the state to prove that the person knew or should have known what they were doing in commiting some culpable act. Not so in sanctions cases. These, instead, are “strict liability”, meaning that the only thing that matters is that you did it. All the onus of making sure you or your entity does not trade (or in Tether’s case, facilitate trade) with blocked persons or countries is on you. Better not fuck up, bucko.

For private citizens this is probably pretty easy. My parents in Maine have no reason to sell Lithium to Venezuela. For businesses, though, and particularly financial service businesses, it can be incredibly difficult (or practically impossible) to comply. This is because the nature of financial services is to constantly intermediate large numbers of transactions, and even with standard KYC/AML, it is essentially certain that these transactions will at least occasionally contact some of the thousands of persons and entities on the sanctions lists and the millions of citizens of blocked countries.

This has a few consequences. First, OFAC and DOJ could probably construct a winning sanctions violation case against any financial services business in the United States at any time if they wanted to, giving them essentially plenary authority to set the rules of conduct and enforce their will on the industry. Second, in order to implement an agenda of actual sanctions compliance, OFAC disseminates materials that guide companies on best practices to keep them as close to compliance as possible. Entities that closely follow these guidelines will not know that they are in compliance, bear in mind, but they will hope that their good faith effort is sufficient to stave off prosecution.

What are the Implications of this Investigation?

So now, DOJ and OFAC have turned their watchful gaze to Tether, noting, according to WSJ, that USDT is used by “the terrorist group Hamas and Russian arms dealers.” WSJ also separately reported that USDT is a “vital financial tool” for the “North Korean nuclear-weapons program, Mexican drug cartels, Russian arms companies, Middle Eastern terrorist groups and Chinese manufacturers of chemicals used to make fentanyl.” All that is bad! Of course, it is impossible to pass on whether or not these claims are true, but it is entirely plausible that any highly liquid stablecoin could be used to facilitate trade among entities, individuals, and states which otherwise would be prohibited from accessing the Western financial system.

Tether has said that it is not aware of any investigation, and emphasized the controls that it currently has in place to prevent this kind of activity. But the upside of reading this newsletter should be this: if OFAC and DOJ want to killshot Tether, and indeed nearly any other stablecoin issuer, they likely can. It doesn’t matter how much compliance Tether does, there will probably always be enough illicit usage to justify any penalty scheme the government wishes to impose.

The truth is, if the same standard of compliance was applied to fiat currency, USD would plainly be just as vulnerable to enforcement as USDT. The historical nature of currency is to serve as an anonymous medium of exchange. Governments, however, aren’t so much fans of the anonymity of it all, and for wholly valid reasons have implemented rules to prevent the digital economy of modernity from retaining this feature.

Cryptocurrency tried to create workarounds to retain individual sovereignty from state-required permission to transact, but this, for obvious reasons, attracted exactly the individuals, entities, and states whose ability to transact had been curtailed by modern digital economies. Over time, governments took notice.

Tether currently holds roughly $100 billion in income generating collateral, with limited attendant costs or obligations to its users. This generated in excess of $5 billion of profit in the first half of 2024 alone, with a team, reportedly, of fewer than 150 employees. It is, effectively, a massive unregulated retail bank—and probably one of the world's greatest operating businesses. However, as long as its compliance obligations are less than those of Western banks, it will marginally reduce the global authority of the United States government. One may query how long that state of affairs is likely to last.

For now, it's still kicking. And so are we at Brogan Law, staying apprised of the latest industry news—until next week!

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.

To be fair, in an age of high interest rates, popular stablecoins are essentially licenses to print money. It is fair to guess some additional compliance costs could be absorbed by competitor stablecoin issuers like Circle without being passed on to users or the industry at large. This is because, generally, stablecoins pay no interest, but on the back end hold income generating assets like Treasury Bills. The more stablecoins that are issued, the more free money accrues to the issuers. Its a great business.

“Mostly” is doing a lot of work here. A natural characteristic of “demand deposits” (like retail banking accounts or stablecoins) collateralized at less than a 1:1 in-kind ratio is to “run.” This is because of the fundamental incentive structure embedded in this kind of system. If I deposit my cash at a bank, and I start to worry the bank might run out of cash and not be able to pay me back, I have powerful incentives to run to the bank and take my money out as quickly as possible, before other bank depositors are able to. Indeed every depositor can have the same incentive simultaneously, leading to “bank runs” where on-hand reserves can be quickly depleted and fire-sales of income generating assets, and bankruptcy, can quickly follow. This was most recently seen at Silicon Valley Bank, and at the stablecoin TerraUSD (though there were other dynamics at play there as well), and it will happen again. Retail deposit banks in the United States are generally shielded from runs by FDIC insurance, which, by backstopping the banks deposits, removes the shared incentive of bank depositors to run to withdraw their money in times of contagion. In this way, the FDIC prevents runs from happening in the first place. Stablecoins don’t have FDIC insurance, though, so they are vulnerable to runs. The degree of this vulnerability may be lessened by maintaining highly liquid reserves, and relatively high ratios of in-kind collateralization, but if the collateralization is anything less than 1:1 in-kind the risk will remain. A constant risk over a long enough period is, remember, a certainty.

This is why, after the United States and Europe imposed several sanctions on Russia following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russian trade increasingly passed through countries like Iran and North Korea. Since they were already sanctioned, United States secondary sanctions could no longer serve as a deterrent. In this way, sanctions can have a negative network effect on their policy goals. The more countries added to the sanctions list, the greater the potential avenues for trade become between those sanctioned countries.

US Persons does not mean “citizens of the United States” but rather is a term of art defined by law, sometimes differently for different sanctions regimes. While this is complicated, it basically means citizens, permanent residents, persons in the United States, entities organized or doing business in the United States, or foreign subsidiaries of businesses formed in the United States.