Bill Hughes Knows Washington

In a wide-ranging interview, Consensys Director of Global Regulatory Matters Bill Hughes explains the recent IRS rulemaking, crypto's policy future, and the inside game of Washington D.C.

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

Tomorrow, Donald Trump will be inaugurated as the 47th President of the United States. Cryptocurrency has already become one of this new administration’s signature policies. Just this Friday, many of you attended the “Crypto Ball” in Washington D.C. and feted the great work the industry has done to regain standing in the United States.1

Obviously, this is incredibly important, and what comes after the inauguration will shape our industry’s fate forever. But I have no idea what that future is, and neither does anyone else. So, let’s talk policy instead.

When Donald Trump won in November, many cryptocurrency operators breathed a sigh of relief. The Biden administration, perhaps in the sway of Elizabeth Warren and her cabal of former staffers and allies, engaged in a well-documented campaign against the industry, and Trump promised to end it. Yet, even in the twilight of the lame duck, the Biden administration continued lobbing grenades.

On December 27, 2024, the IRS finalized rulemaking in Gross Proceeds Reporting by Brokers that Regularly Provide Services Effectuating Digital Asset Sales (the “IRS Rule”). The rule, which would vastly expand the reporting burden of virtually all of DeFi, has been percolating since 2021. The industry balked when a version of it was first proposed in 2023, and the electorate repudiated the Biden administration in November, but the IRS went forward anyway.2

This is bad! So, this week we’re talking to someone on the frontlines. Bill Hughes has been championing this issue for crypto through public channels for years. He is senior counsel and director of global regulatory matters at Consensys and a board member of the Blockchain Association (BA). Prior to his roles in crypto, he served in the Justice Department as associate deputy attorney general from 2019-21, and as deputy director in the Executive Office of the President from 2017-19. Incidentally, he is also strikingly smart and an excellent follow on X. Washington D.C. may not be so many smoke-filled rooms as it once was, but sometimes you still need an expert to find its stochastic pulse.

Bill Hughes is the perfect person for that. Let’s get into it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Nothing herein is legal advice.

Aaron Brogan: Bill, thank you for joining us. Brogan Law clients and readers are all intently interested in the world of Washington D.C., both the background of how these regulations get made and especially how interested groups can push back against them and develop better policy. There are few more qualified than you to speak on this. So, to start, could you give my readers a little bit of background about yourself, your role, and what you stand for?

Bill Hughes: [LAUGHS] What I stand for? Peace, love, and the American way.

I’ve been with ConenSys for three and a half years. I'm primarily an in-house lawyer. We have small legal team here. Consensys is a software developer with 300 folks in the United States and four to five hundred overseas. The software we make is primarily designed for the Ethereum and other interoperable programmable blockchain ecosystems. our biggest product is MetaMask, which is a self-custody wallet, and lots of services and functionalities built into that wallet. and our, our biggest customers are both regular retail consumers but also a lot of software developers who use our offering to actually build their own apps and services

My role at the company is primarily to help the company navigate regulatory risk. We are not a financial institution, we're not an intermediary, but our software, in large part, is starting to replace intermediaries, so there's lots of policy issues about (i) what’s the risk profile of people using this software, (ii) what risks to consumers does using the software entail? And (iii) what does public policy need to do to mitigate those risks? I do basically everything in terms of legal advice at the company.

Prior to Consensys I was at the Department of Justice. I worked in leadership and had a broad portfolio of both civil and criminal matters. And I did a lot on the, let's say, rulemaking front. DOJ is always brought into different rules and regulations that the executive branch is working on to provide both a legal and a policy review of those prior to them being finalized. I did that for two years, and prior to that I was at the White House where I really had an operational role. I wasn’t serving as a lawyer. I ran one of the offices in the Executive Office of the President that really was the operational and administrative backbone for the entire executive office of the President.

Aaron Brogan: So the reason that I asked you to be here is a very specific policy issue. In December we saw the IRS promulgate final rulemaking regarding reporting requirements for DeFi institutions. Classifying them as a broker, this rulemaking is called “Gross Proceeds Reporting by Brokers that Regularly Provide Services Effectuating Digital Asset Sales.” It's a mouthful. I call it the IRS Rule. So can you explain a little bit of the statutory history, this rulemaking, and then why this is such a problem for the cryptocurrency industry?

Bill Hughes: Sure. So, way back in Summer 2021 I spent some meaningful hours during a vacation at the beach on the phone with folks at the company and on Capitol Hill talking about the Infrastructure and Jobs Act (ILJA), which has nothing to do with infrastructure or jobs.

That was because one of the provisions sought to codify a practice that some centralized exchanges were already engaged in. That was essentially helping users keep tabs of their reportable gains from buying and selling crypto on their platforms. It's a feature of some of these big exchanges, like Coinbase. At the end of the year they make reporting taxable gains easy for you because they have a record of all your transactions and can internally keep track of your cost basis and figure out if you sold something and whether there any gains to report. This was all done because the market was trying to address a user demand. They actually weren't technically required to do it.

So this provision was added to the ILJA In order to require them under the tax code to provide this tax reporting. The genesis of it, as I'm told, is that IRS comes up with a figure as to how many billions of dollars of taxes are not getting paid because reporting isn't sufficient, and they apparently came up with 30 billion dollars. Now the ILJA was a huge spending bill, and, when you're trying to get a spending bill through, it certainly makes it a lot easier to get people to hold their nose and vote yes when you can find ways to raise revenue in the same bill—they're called “pay-fors.” So, I can spend all this money over here if I'm taking more money in over there.

So they added this provision and this provision basically said that if you're effectuating transactions for somebody like Coinbase you have to (i) give the user their data their information on a trade-by-trade basis, and (ii) you have to report it to the IRS.

Now, it was reported at the time that the Treasury officials purposely wanted the language to be pretty broad as to what constitutes a broker. The thinking at the time was that Treasury folks—who were very influenced by this anti-crypto or at the very least crypto-skeptic worldview—thought if the language was broad enough, they would not only be able to hold Coinbase’s feet to the fire, they could also expand the number of entities in the ecosystem that would then be required to track activity and report.

So the law goes into effect and IRS takes a long time putting out a rulemaking on it. That notice of proposed rulemaking goes out years ago and everybody under the sun comments on it. We put in a lot of time and effort at Consensys to comment on it because it was clear in the notice of proposed rulemaking that they were not only saying Coinbase and actual institutional brokerages, that have customer accounts and trade on their behalf, were included, but that they intended to include DeFi. And basically, they saw that even though the vast majority of the economic activity was being done on centralized exchanges that DeFi was something that they wanted to pull into the law.

They had to bend themselves into a pretzel with these rhetorical gymnastics to get a broker—someone who effectuates trades—to be, basically, anybody who has the ability to know about trades. So the rule went into this weird Russian-nesting-doll approach to interpreting, and defining terms, so the actual implication of all of that logic was that the term “effectuates” now means something completely different.

They finalized the first part of the rule last summer and that part of the rule focuses on CeFi. And that part was overly broad and overly burdensome in many respects, but at least Coinbase is already kind of doing this and the problem is around the margins. Then they say, “we're putting off the DeFi stuff until later.” And there was some question of if they were just punting on this completely or whether they are eventually going to put something out. They then put something out after the election and it effectively said front-end interfaces through which people access swap, smart contract protocols, etc., are brokers because they are effectuating trades. It's broader than that but they were very clear that this is a special category of interface.

Aaron Brogan: And those frond-end interfaces are, e.g., the Uniswap front end that gives access to an on-chain protocol?

Bill Hughes: So it’s the Uniswap front-end, it's the Swaps functionality inside MetaMask, it's anything where there's an interface where a user can, on their own, punch in one token, then the amount, and select another token they want it to be swapped into and then send off that transaction on their own. So that's clearly within the ambit of what the new rule purports to require reporting on.

Aaron Brogan: But it's even broader than that too, right?

Bill Hughes: It is broader than that, but the thrust of the activity that they're looking to capture is that. Moreover, they're also looking for reporting on transactions and stable coins. Which, you’ve got to ask, is the juice worth the squeeze? Those transactions are fractions and fractions and fractions of a penny every time. You really want all that reporting?

These points were made to the IRS, including by me in person at the Treasury building, and they dutifully wrote down notes about these points and, apparently, they were unavailing because they kept it in the rule.

They also wanted reporting on NFT trading, even though they don't as a general matter require reporting on trading of baseball cards. So the rule is terribly expansive and the real problem is that none of these software companies are built to do this stuff. It's disruptive to the business model and to say it is potentially existentially burdensome on many of these entities is an understatement.

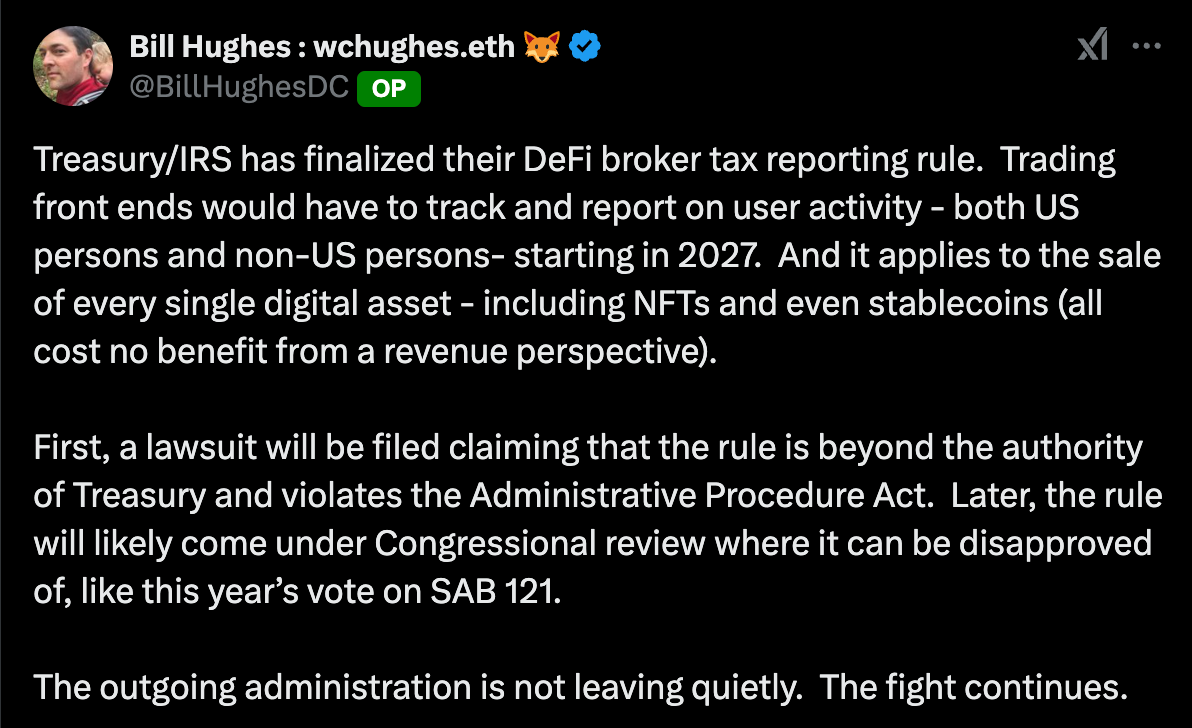

Aaron Brogan: I want to talk a little bit about the process of promulgating a rule after the election, at the end of December, which is sometimes called, “Midnight Rulemaking.” You’ve previously said, I'm quoting a xeet from December 27th, that “the outgoing administration is not leaving quietly.” For people who aren't Washington people, this is not as legible as it might be to people in Washington because it seems that Trump's coming in and he's going to be in charge and can change the rules. What is the relative durability of these IRS Rules?

Bill Hughes: Simply put, if there's a process to engage in rulemaking to finalize a rule, to rescind the rule you can't do that without going through process as well. So, you can't just say “this rule is being deleted from the Federal Register” because someone will sue you over it arguing that was arbitrary and capricious. Rescinding the rule is like putting out another rule in terms of process. There are no shortcuts—so it takes away time, personnel bandwidth, mental bandwidth. The other parts of your policy agenda have to be set aside or delayed for you to engage in this cleanup work at the front end.

Some rules are probably contrary to the incoming administration's policy on the issues. Nevertheless, agencies try to drag them across the finish line, so the next administration has to deal with them and has to go through a process of rescinding them.

That process could take several approaches. One, because it's so late in the calendar year, you can have the next Congress take up their time to try to get both houses to vote on whether the Congress should disapprove of the rule.

Aaron Brogan: And this is the Congressional Review Act (CRA)?

Bill Hughes: The Congressional Review Act says that if Congress goes through the process, not only does that vacate the rule, but the agency is forbidden from promulgating something that is even similar to it. So it's a pretty good process. It's a burdensome, but pretty powerful remedy

The second thing you could do is engage in rescinding the rule, which requires the agency in most cases to put out, essentially, a new notice of proposed rulemaking saying that that rule is done and providing a period of 30 or 60 days from when the proposal is printed in the Federal Register for the public to send in comments as to why the agency shouldn't rescind the rule. The agency then has to consider those and write up this whole long paper as to why they're considered. And so that that takes a long time.

Another thing a presidential administration can do, because it's less draining on federal resources, is let the private sector sue for an injunction of the rule, and a court may vacate the rule for violating some law. This could be the Administrative Procedure Act, some other substantive statute, or the Constitution. What the administration can do is say, “DOJ, you're not defending this lawsuit.” You can just stand there and let the other party make all the arguments and say “Judge, we've got nothing to say on this.” So basically, in those instances, the administration is expecting the court to issue an injunction to vacate the rule, and then the administration can just do nothing. You don't try to resurrect the rule by fixing the problems in it. You just have a standing injunction blocking the rule and then everybody goes about their business with the rest of the policy agenda.

So, there's basically three different ways to do it. It looks like the CRA stuff is going to be the first bite at the apple in terms of rolling this IRS Rule back.

Aaron Brogan: Yeah, so let's talk about this. The CRA requires both the Senate and House, both of which are controlled by Republicans, and then it goes to Trump, who presumably would be willing to sign it. Do you see any roadblocks to that? Or do you think it's the most likely path forward?

Bill Hughes: There are just finite resources, which could lead to it not getting its time on the floor because there are too many other things to do. The scenario would be that Congress can't do this now because the party and the President have their priorities and there are only so many times you can have floor votes. There are a lot of really important things that are competing for the attention of the House and the Senate.

So, how the CRA would proceed. It’s a little more complicated than Ted Cruz walking in, whistling, getting everyone's attention, holding up a piece of paper and having everybody go “aye”, then walking it down to the White House saying “Hey, boss, can you sign this real quick?” It doesn't work that way. We'll see how it plays out.

At the end of the day, is the industry 100% counting on this thing to be rolled back? Yes. It would be nice to do so in as efficient a manner as possible and, as a director of the Board of the Blockchain Association, it would be nice to do so in a way that's not costing us money that could be better spent on more productive things.

Aaron Brogan: Can you talk a little bit about the Blockchain Association litigation? The BA, along with co-plaintiffs the DeFi Education Fund and Texas Blockchain Council, filed it the day this rule came out or shortly thereafter.

Bill Hughes: Almost like we were ready for it. Almost like we were expecting it.

Aaron Brogan: Obviously, BA litigation has been very fruitful in the past. In this case, what do you think the strongest arguments, in our Loper-Bright world, is for this complaint?

Bill Hughes: The clear argument is that they are mangling the proper interpretation of what the statute permits them to do by saying brokers effectuate transactions. They are reimagining what effectuate means in order to expand the scope of people who fall within these reporting obligations, and that just is plainly impermissible.

[NOTE: The statutory language being discussed is as follows: A broker means “any person who (for consideration) is responsible for regularly providing any service effectuating transfers of digital assets on behalf of another person.”]

Remember, Loper Bright undoes Chevron. What did Chevron say? If a statute is ambiguous, and the agencies interpretation of the ambiguity is reasonable, then you should be deferring to the agency because they’re experts. Loper Bright says no, you shouldn't just blindly defer to a reasonable interpretation by the agency, but it comes down to whether the statute is ambiguous. I'd argue it's not. If you just read the rule, you can see how far they have to extend the logic to do what they want to do.

You see the departure point, “effectuate”, and the arrival point, which is quite clearly far afield from what effectuate means. You don’t even have to get to questions of deference. If those notions of jurisprudence still pertained, you wouldn’t even need to get there. It's clear they’re misreading the statute in order to pull more of this stuff into their reporting regime.

And so, we are glad to be in a district court in the Fifth Circuit, but is it necessary to be in a more administratively skeptical circuit in order to get a good ruling vacating this rule? I don't think so. If we went along with the litigation, they wouldn't need to get to all these sorts of secondary and tertiary arguments. Very clearly they’re misapplying the statute to a cohort which goes far beyond what the plain language of the statute says.

Aaron Brogan: There's another thing here, which is that Trump had tax cuts in 2017, those are expiring at the end of 2025. Mike Johnson has said there's going to be one, big, beautiful bill, in 2025, which I think goes through the reconciliation process and you basically just put everything in the world in there. Do you think that's a vector to try to fix these tax rules?

Bill Hughes: Currently, there's not a ton of discussion about trying to inject crypto-specific provisions into that effort. I'm going to encourage my colleagues to seriously consider advocating for provisions in the larger bill that get at, maybe not sexy, but fundamental and important policies that would be sensible for revenue generation and sensible for the functioning of the crypto ecosystem. That would include reporting things, but would go beyond that, would go to things like a de minimis exemption, which pertains to currencies when you're not spending more than like five, six-hundred bucks at a time. There are a number of things that we can patch together in one title in this larger bill, which would really advance the ball on a number of fronts.

I think it's worth pursuing. Right now, it's not being discussed. And it may simply not be something that is important enough to get the really important decision makers on board, to have another thing to debate in a bill that is already going to be heavily debated on a number of different fronts. So we'll see, but the tax stuff is very important. Reporting taxable gains is one aspect of it, but there are lots of things that we need to clean up.

Aaron Brogan: Yeah, that's the good place to pivot into policy. The way that DeFi works right now is there's a degree of permissionless-ness and decentralization that are inconsistent with front end KYC of collecting documents. There's a pseudonymity aspect, which is inconsistent with collecting tax documents. And on a certain level, while enterprise is positive sum, power is zero sum, so there's a conflict between a government that wants to use financial intermediaries to oversee these transactions, and then on the other hand, an industry which is disintermediated and doesn't collect documents. Is there a path to reconcile this in your view?

Bill Hughes: I think what we're going to see over the course of the coming years, we're already starting to see it now, is a distinction between services and products. Businesses that provide services are regulated all the time. Products, their safety can be regulated too, but less frequently.

Right now, services, like providing a managed front-end interface that permits people to compose and sign-and-send swap transactions, for example. That is not regulated under law currently. And the question is should it be regulated? The SEC's argument is that it is already regulated, the Gary Gensler administration took the position that: “Yes, these services are already regulated under the Securities Act. You guys have just failed to comply with the current regulations that already applied.” But that argument is dying because the SEC's policies on that are going to be changing, are changing right now.

This is the great controversy in this space. Can you run a business, or should you be able to run on business, that has the ability to collect all this information and report it—to gatekeep and monitor, to push back against things like illicit finance and market manipulation and stuff like that. You could be able to, but should you be required to?

I think that where this ultimately ends up is that if you're running a for-profit business that is offering these services, there's going to be some degree of gatekeeping and monitoring that you will be required to do. You will be deputized in some manner to fight back against illicit finance or market manipulation or something like that. The question is, what precisely are you going to be required to do? Is it going to be full-blown KYC transaction monitoring like a normal financial institution does? I think that that would be a mistake because then that really would be converting these software companies into financial intermediaries.

Is there something less than that that is enough to mitigate the risks and mitigate the threats of illicit finance and other illegal activity? I think so. In a way that doesn't require ballooning fees to help pay to cover compliance costs? I think so. And we should pursue those. We don't really like to talk about them because we're committed as an industry to an ideal of the industry as un-owned open-source software that does all this stuff.

The problem is, it's not. MetaMask, the wallet itself, is open-source software. You can license and reproduce up to 10,000 iterations of it without needing any other agreement from us. The services built into it are managed services which currently aren't regulated. Will it be the most offensive thing to have a company like Conesensys or a company like Uniswap Labs, who are offering services which are operated in part through software that is operating off a cloud that we pay for? I don't think so. But the devil is in the details as to what precisely we would have to do.

There is going to be a line when it comes to open-source, unowned, freely usable software, either on Github or on the blockchain. Regulating that stuff like you would proprietary software certainly seems to everybody like a bridge too far.

Aaron Brogan: So here's a question. If you take my premise that it is disempowering to these financial regulators to a certain degree, is that a desirable outcome or is it undermining controls?

Bill Hughes: I think it's preferable to change the markets such that the risks requiring supervision and requiring intervention are reduced because of the way the market works, thus obviating the need for the agency to do everything that it is currently doing.

The purpose is not to create a system which makes it impossible for a regulator to do what it's doing, but it still needs to do it. The purpose of the ecosystem is to remove the risks that underlie a lot of the authority and functions of the regulator to begin with. The regulator was necessary to mitigate certain risks which in a disintermediate ecosystem are now no longer present.

Now, to the extent that there are new risks or the risks have been modified and improved upon but not completely gone away, the question becomes, well, does the purview and the authority of the regulator need to adapt to neatly fit the new risk landscape? Not that they need to go away but maybe what they're doing needs to be a little bit different. Maybe a little bit lighter touch. I would flip it on its head. This isn't about defanging regulators, so they can't do what needs to be done. It's removing problems from their job jar.

Aaron Brogan: Cool. Well I have just one more policy question and it's something that I asked everyone who's come on and been interviewed. Because, you know, I think it's an age-old question in cryptocurrency. I think there's been a preference among practitioners in the space for the CFTC, as the regulator of cryptocurrency, versus the SEC. Maybe it was because the Benham CFTC was less aggressive than the Gensler SEC was. In your view, from first principles, should the industry prefer one or the other? And why do you think that is?

Bill Hughes: I don't have a view as to who they should prefer. People prefer who they want. But let me just make some observations on why the CFTC has been preferred. CFTC supervision is just less onerous than the SEC supervision. I know many people who have worked at companies that have been regulated by each and they say it's night and day. Life is easier having to answer to the CFTC than it is to the SEC.

The second thing is quite clearly a product of the CFTC not being dovish, but not being outwardly hostile, and the SEC being scorched earth, get off my lawn, you shall not pass with Crypto. There have been commenters on Twitter and elsewhere who have consistently observed, I think correctly, that the Commodity Exchange Act and the CFTC regulations are built around markets which are pervasively intermediated. You can't just buy and sell futures contracts or derivatives peer-to-peer. Everything has to go through the prescribed pipes in the market. That is not true with securities. It's much more laissez-faire. It's much more peer-to-peer. So that's a concern.

Another thing is the CFTC doesn’t regulate spot anything. They have fraud enforcement authority over spot markets to the extent that they impact markets that they directly regulate, but they don't regulate stuff the average consumer just buys themselves. The SEC does. Which is part of the reason why they're much bigger. So there is a sort of institutional history to the SEC maybe being more capable of regulating retail facing markets where there is a lot of grassroots engagement directly with the market itself rather than through intermediaries.

My sense is that big exchanges want, to the extent spot trading on a centralized exchange is a regulated activity—even though let's say all of the tokens are commodities—they want the CFTC to regulate the spot exchanges. That would be a new job for the CFTC and you know, who says they're not up for, but it would be new. And there's been a big push in DC both in the last couple months in the lame duck, and certainly, as the New Year kicks off to get that done. We'll see if it gets done.

Aaron Brogan: Well, thank you for your time Bill. It's been it's been really illuminating, and I know that my readers and clients are going to be really excited to read it. I give people a last question, if there's anything you want to add, something I forgot, talk about the Washington Commanders, whatever you want to talk about.

Bill Hughes: This weekend is the divisional round of the NFL playoffs, which the Commanders haven't been in in 19 years. I go into every playoff game not expecting the best, and that keeps me sane and keeps my hair from falling out—so I will be celebrating and not expecting to do anything after the game other than celebrate. It’s been a truly amazing season and looking forward to next year. But we'll see how it goes.

[Editor’s Note: A few days after this interview, the Commanders defeated the Detroit Lions 45-31 to advance to the NFC Championship.]

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.

Congratulations if you bought $TRUMP.

For more coverage of the IRS Rule, check out the Brogan Law writeup from a few weeks ago.