Circle's S-1, Annotated

Oh, and some thoughts on the tariffs too.

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

Tariffs

Listen, this is a cryptocurrency law newsletter. We don’t talk about macro-trends or the economy at large unless it touches on crypto. But if I sat here and wrote about the Circle S-1 without mentioning the massive economic upheaval going on, I’d feel like a doofus.

I think the tariff program Donald Trump announced after markets closed Wednesday is ill-advised. Mr. Trump has advocated for tariffs since before his political career began. He takes the view that trade deficits indicate the United States is being treated unfairly, and that tariffs are a tool to correct this.

I disagree with that. I think when we buy things as an economy, it is because we receive more value in return than we give up in the trade. The fact that money is leaving the economy isn’t particularly important because value is coming back. And money, after all, is just an instantiation of value.

By sending some value out and getting more back, we generated consumer surplus and became rich.

I think it is good to be rich.

At a micro-level, it is true that there are losers to trade. In a free trade system, domestic producers compete with foreign surrogates with lower fixed costs. This can drive automation and innovation, increasing productivity, but it can also make domestic businesses uncompetitive and eventually dead. That’s a problem because (i) individuals who work in these industries have invested in developing specialized human capital, and that human capital becomes worthless when the industries fail, and; (ii) nations that outsource their physical production capacity lose resilience to military conflict.

It’s clear, in my view, that this happened in the United States over the past thirty years, and really since the Nixon shock of 1971. While our military size on paper remained relatively stable, our military capacity declined dramatically. In part, this might have been through cost-plus contracting models and mismanagement, but more meaningfully I think it was because our civilian capacity declined, and military capacity is largely just a function of that.

And if, for the past thirty to fifty years, we had maintained higher barriers to trade, this may not have happened. But we didn’t, and there is nothing we can do about that now.

China, for many years, has engaged in currency manipulation and dumping, likely specifically with the intent to hollow out other nations’ productive capacity. This merits a response, and Mr. Trump’s first trade war was justified. To take one example, the United States needs a domestic drone industry to meaningfully participate in 21st century military conflict, and there is no way that a domestic drone industry will develop without tariffing DJI. If I was in charge, I would protect Tesla and impose trade barriers to Chinese finished goods and batteries. We need more industrial policy than just that, but trade matters.

But Mr. Trump chose trade war not just with China, but with the whole world as well, and this, in my view, is foolish. By placing confiscatory barriers to trade on nearly all of our trading partners, Trump has essentially chosen to sanction the United States. If you look at the history of countries that have been isolated from global trade through sanctions, Cuba, Venezuela, Iran, North Korea, the result, in the medium-term, has been shortages and immiseration.

Now, I think Mr. Trump will blink before famine comes, but we will not return to the global order with the same standing as when we left. The administration is right that the world will feel pain from our leaving, but the world can substitute for our demand amongst themselves, while we will atrophy alone. If you bully your allies for long enough they will become your adversaries. There is no law of nature that France or Canada has to support the United States in a conflict with China.

The United States spent the last eighty years integrating itself into the economies of the great powers of the world. As Mr. Trump has adroitly identified, this gives it leverage—equity. But that equity is not permanent. If you spend it, it is gone. On Wednesday, the United States began to spend its equity down. Continue long enough, and much like Russia, we will have nothing left but the bomb.

Personally, I find such cavalier wasting of our security apparatus alarming, much as I find threats directed at our allies Canada and Denmark alarming. The United States is the strongest or second strongest nation in the world, but if we fight all of the world, we will be destroyed. And precisely because of our massive nuclear stockpile, the incentives for a conquering power will not be to allow the United States to limp away, but rather to completely dominate and overcome us. We are relatively secure today, but by becoming the biggest kid in the school yard, we have made ourselves peculiarly vulnerable. And in a war with China, if our defensive capabilities were ever overwhelmed, we could live to see our way of life destroyed for good.

Fundamentally, I think, Mr. Trump and his close supporters don't believe or understand this. They don’t think preserving strength and influence matters, because we are already the strongest. But the same could have been said about every other great power in history, and each fell in its time. If it were mine to run, I would keep a paranoid eye on preserving every conceivable bit of strength for the day it is needed again. Because one way or another, the day is sure to come.

It’s not mine to run, though. These are my objections, but Mr. Trump disagrees with me, and the political system we have for intermediating these choices imbued him with the authority to choose. So, while I think this tariff program will plunge us into recession, make us more vulnerable, and decrease our likelihood of winning the AI arms-race, there is nothing I can do. No legislation to change the tariffs could pass the House, and even if it could, Trump wouldn’t sign it into law.

Now, it comes to cryptocurrency firms like yours to figure out how to do something with this. Ultimately, we all must take the world as it comes to us. Trade barriers will present an incredible opportunity for stateless decentralized software to gain a larger share of global economic activity. You are the ones to build it. There is much pain for all of us on the way, but chaos is a ladder, and those who find ways to climb it will be the winners of the future.

Circle’s S-1, Annotated

The largest stablecoins in circulation are USDC, issued by Circle, and USDT, issued by Tether. In the lore, these two entities are imagined as a good and a bad angel sitting on the industry’s shoulders. Tether was reportedly investigated by the Biden DOJ for sanctions violations, and was cited and fined $41 million in October 2021 by the CFTC for discrepancies between its public statements concerning its collateral reserve and the reserve itself.

Circle, on the other hand, is the model student—generally attempting to comply with regulatory regimes and, other than a reported SEC investigation in 2021, mostly keeping its nose clean.

In use, the products are essentially the same, a collateral backed USD denominated stablecoin that rigidly maintains its peg through all economic weather. Through this process, both firms have minted vast quantities of stablecoins, as of writing $60 billion USDC and $144 billion USDT.

But the instrument’s sameness is actually an illusion—while in use and design they function indistinguishably, a huge portion of their value exists in the back-end reserve practices of their issuers, which range from transparent (Circle) to relatively opaque (Tether). Holders have huge exposure to these entities, because they are, in effect, their counterparties—and so it is worth investigating how they actually work.

Now, the model for being a stablecoin issuer is basically straightforward. For reasons of securities law, Circle and Tether have a plausible argument that they cannot pass on interest to token holders—at least to normal retail stablecoin holders. In order to maintain the tokens, though, they generally have to maintain 1:1 collateral in fairly liquid assets. One model of this is to maintain the reserves in kind, with a vault of dollar bills or something, but this is obviously prohibitively impractical, and has the downside of not making any money.

Instead, stablecoin issuers keep their collateral reserves in the form of highly secure short-dated assets like U.S. Treasury debt, money market funds, repo markets, and similar instruments. This means that they earn something close to the fed funds rate on the money, and basically don’t have to do anything with it.

This is not that high a rate of return, but when you have tens of billions of dollars, it is a lot of money! That’s how Tether, in 2024, reported an insane $13 billion in profit. Leading some (me) to speculate that it might be the greatest business of all time. Making this doubly impressive is that Tether had, until 2025, only an estimated 100 employees.

They know what they do (hold massive reserves of collateral for unsecured retail creditors) and they do that. Incredible business.

Circle, in the past, has been slightly less transparent about its earnings. But it holds roughly 40% of the reserves of Tether, and so it should make, say, 40% of its profit (~$5 billion), right? Wrong. Very, very wrong.

This week, Circle’s initially confidential S-1 filing became public. Back in 2024, Circle wanted to make an initial public offering, and one of the steps to doing that is preparing a prospectus (this is the S-1). Basically, your prospectus includes reasonably detailed, audited financial statements, a bunch of information about your business and, importantly, a detailed list of risk factors. If you miss any, or misstate them, and something goes wrong, people will sue you. This is called prospectus liability and some attorneys are big fans of it.

I’m not sure if Circle will go through with this offering now that the economy is just an endless sequence of red candles. That is probably not ideal timing to test the market. Nonetheless, I went through the S-1 to see what curiosities might be found there. (you can follow along here).

Circle makes less money than you might think.

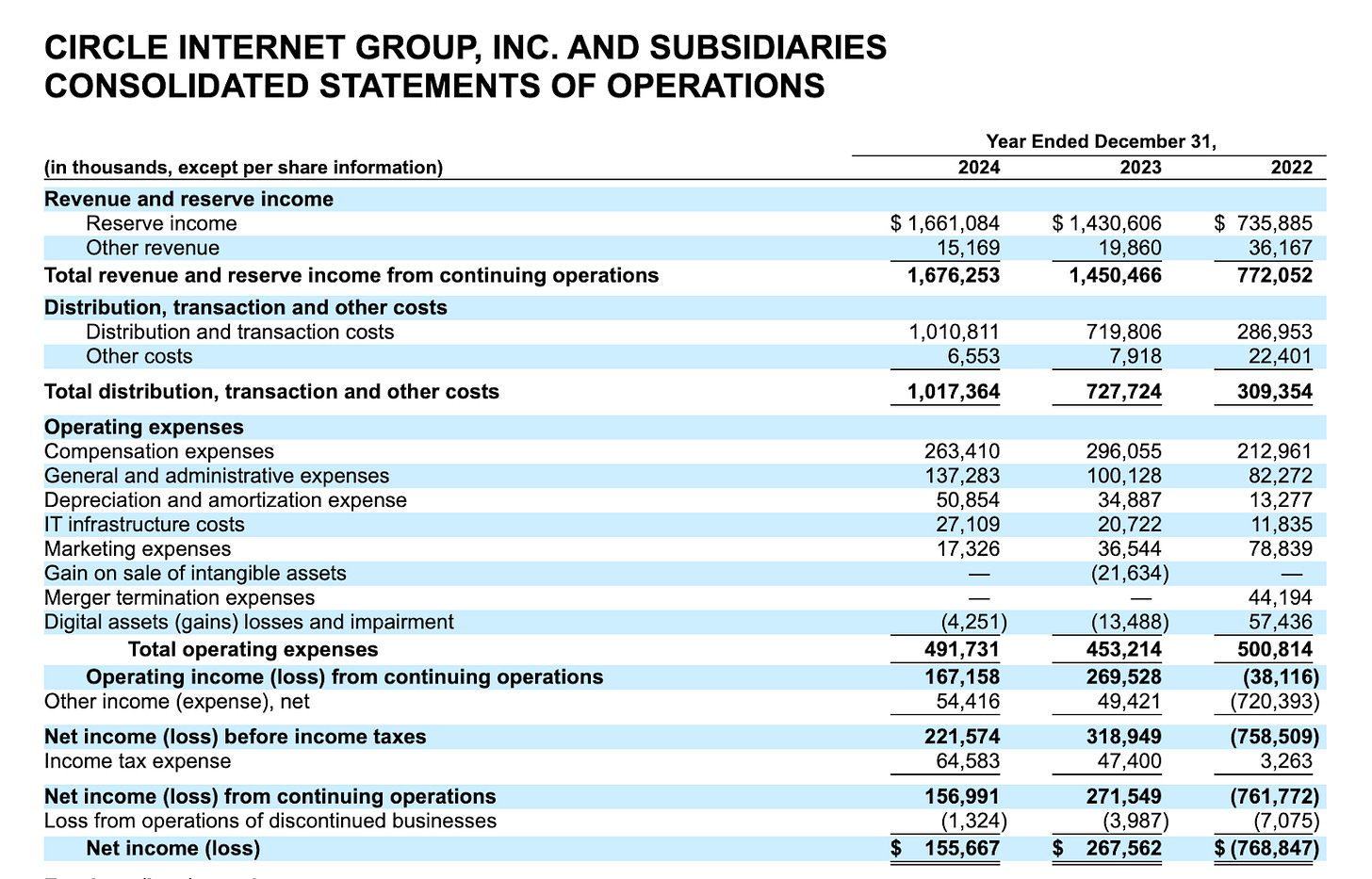

Ok, I lied, they make a ton of money. Circle has revenues ranging in the hundreds of millions (in a relatively low rate environment) to the billions (in the current rate environment). This is combined with significant FTE count (exact number unspecified in S-1), and enormous partnership expenses with both Coinbase and Binance lead them to operate at a loss in 2022, and at a relatively modest $150-300 million profit in ‘23 and ‘24. This is a lot of profit to make! But it is two orders of magnitude less than Tether. I am sure that has to do with risk tolerance, growth models, and regulatory compliance, but still, it must be a little painful.

Despite its compliance, Circle is still exposed to Tether risk.

While Circle goes out of its way to find paths to legal compliance, and has largely succeeded, it did not fall out of a coconut tree, and so it still exists in the context of all that came before it. This means crypto, and all the baggage that goes with it, are still presented as a risk factor in the S-1. Now, risk factors in a prospectus are overbroad by design, but it is nonetheless an interesting vignette of the correlative nature of crypto risks.

Circle’s income is fragile.

One of the major risk factors that Circle identified is exposure to changes in interest rates. As discussed above, in 2022, when interest rates were lower, the firm lost $761.7 million. In 2024, interest or interest-like returns netted the firm 99.1% of its revenues. This is a serious exposure and major risk factor going forward, particularly because Donald Trump is currently reportedly attempting to lower rates! Now, some of Circle's major costs are variable, which could help shelter it from rate pressure in the future, but the core of this business has much greater surface area to rate changes than, say, Tether. A large workforce and various programs are facially good ideas for running a compliant institution-friendly fintech business, but they are liabilities, and if Mr. Powell waves his magic wand and wishes us back to ZIRP land, how long will Circle be able to survive? I don’t know, and that is a concern because…

Circle’s reserves are not necessarily bankruptcy remote.

So when your company goes bankrupt, all of its assets are frozen and put in a pot, and then every creditor gets a certain amount of time to come and submit claims against that pot and those claims are then ranked by order of preference based on a prescribed waterfall generally ordered as follows:

Lawyers and professionals.

First lien, perfected, debt.

Everyone else.

Equity holders.

That’s good because it prevents fire sales of assets, distributes proceeds in an ordered way that promotes certainty and therefore lending, and gives businesses with valuable operations to continue as going concerns.

It’s bad if you’ve deposited your stuff in the company and you need to use it anytime soon, though. Once assets are tied up in bankruptcy proceedings, they can be trapped there for years, being slowly dissipated in the form of professional fees. This is always annoying, but it is especially annoying if the assets are generally liquid capital adjuncts that you were hoping to use for things, as was the case in the wave of cryptocurrency bankruptcies in 2022.

But there is an out to this, which is that if assets are held in trust, for the benefit of a user, then they are not considered “company property”, but rather user property, and that means, in turn, that they aren’t subject to the automatic stay and can be more or less immediately distributed back to users, unimpaired. This is really good! But in order to gain this status, companies have to meticulously maintain the assets outside of its operating accounts, and generally fulfill any number of other formalities. Importantly, if they don’t do that, even if they tell you they are doing it, then your assets might be considered estate property, and you have to file a claim.

I have no idea if Circle reserves are likely to be considered bankruptcy remote, and while it is likely they put significant effort into maintaining them in this way, they do not know either. A bankruptcy judge could rule the other way easily, and so lock up the entire massive pool of reserves indefinitely in the event of a bankruptcy.

This is a pretty remote risk, because the vast, vast majority of liabilities on Circle’s balance sheet are unsecured claims on these reserves, but if there is a real risk of the company becoming cash flow insolvent (if, for instance, interest rates go to zero and they don’t fire their workforce fast enough), then this is something to chew on.

Circle has some Coinbase exposure.

Back in 2018, when Circle was still quite small, it established a “Centre Consortium” joint venture with Coinbase. Coinbase then made an investment in Circle and in 2023 the two parties executed a “Collaboration Agreement” which essentially entailed Circle giving Coinbase half of the returns on its business in exchange for distribution. This is a lot of money to give out!

Interestingly, though, the agreement does not stop at this income sharing. It also includes language concerning the USDC and related trademarks which, when very specific circumstances occur, can “flip” to Coinbase, and preclude Circle from issuing further USD denominated stablecoins. Those circumstances are:

Circle determines in good faith that the payment provisions under their Collaboration Agreement with Coinbase would violate applicable law or government order;

A court order prohibits Circle from continuing to satisfy its payment obligations under the Collaboration Agreement, and this violation cannot be remedied by mutual agreement or by restructuring operations within a certain restructuring period;

Circle fails to resume payment obligations under the Collaboration Agreement following such a restructuring period.

It is very difficult to precisely handicap the likelihood of this sequence of events happening, but my prior is that it is probably quite low. That said, it sure feels like Circle is a Coinbase subcontractor, and not the other way around!

Admission of Ignorance

Usually, I read every document I describe here closely, but this S-1 is 250 pages long, and I admit I skimmed parts of it. That is to say, these items are presented as curio more than a definitive analysis of the prospectus as a whole. A faithful account could not fit in a newsletter and so I have left many things out. Moreover, absolutely none of the above is legal or investment advice.

I think the above gives a somewhat bearish portrait of Circle, and maybe it does—at least relative to Tether. Nonetheless, Circle is flourishing as the world’s second largest stablecoin issuer, and that is one of the best businesses ever devised. If the GENIUS Act sponsors get their way and “payment stablecoins” are definitively prohibited from offering yield, then this business will continue to be lucrative in times of high interest in perpetuity.

Still, I worry about low interest rates’ effect on the major issuers, and the risks that poses to the cryptocurrency ecosystem as a whole. A close analysis of these risks will have to wait for another day though.

Until next week.

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.

Hello, thank you for this insight. You mentioned that Circle’s reserves might not be bankruptcy-remote, meaning USDC holders could be stuck waiting years as unsecured creditors in a liquidation. If that happened, wouldn’t USDC’s peg crash almost instantly, causing a liquidity crisis ? With how USDC is used across DeFi and exchanges, it looks like a huge risk for the entire crypto market.Is this a realistic danger, or am I overreacting?