GG Gary Gensler, GG

Chair Gensler is Out, Kalshi is Allegedly Outed, and the Blockchain Association is Outstanding in Texas.

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with legal questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

A Shameless Plug

This is self-serving so I’ll keep it brief. My book, Let the Big Dog Eat, will be published by Velo Press this Tuesday, November 26. It is a quite good book, I think, but it has nothing to do with cryptocurrency or law. It’s about golf, and Maine, and some other stuff too, but mostly it’s about golf—playing it, enjoying it, improving at it. You can pre-order it in paperback or Kindle on Amazon now. If you enjoy my writing here, I hope you give it a look. It’s fun!

Gary Gensler is Out

As expected, SEC Chair Gary Gensler announced this week that he would step down from the Commission on inauguration day, January 20, 2025. Virtually every chair participates in this ritual, as I have written here before, so the news, while welcome for many in the industry, has been adequately covered. Trump is going to get to choose his SEC, and through those choices he will have substantial influence on its enforcement policy over the next four years.

This is not necessarily a panacea for the industry—after all, Jay Clayton, Trump’s previous SEC chair, was not exactly easy on crypto. Still, given the recent politicization of the industry, I think it is reasonable to expect that the incoming Commission will be quite favorable. What that means, exactly, we don’t know yet, so we’ll cover this issue in more depth when more is known about the incoming Commissioner(s).

So, Kalshi may not like Polymarket very much…

After the FBI raid of Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan’s Manhattan residence last week, there has been an inevitable stream of speculation about the case on social media. According to Pirate Wire’s Mike Solana, some of that stream may be less than organic.

In an article published this Friday, November 22, Solana references a number of “screenshots” that he says show behind the scenes evidence of Kalshi or its representatives paying or otherwise compelling influencers to publicly smear Polymarket and Mr. Coplan.

In the only example included directly in the article, a text thread shows someone that Mr. Solana claims is Kalshi employee Keaton Ingles requesting that former NFL player Antonio Brown suggest Mr. Coplan “seem guilty.”

Antonio Brown did indeed post this on November 15, 2024. In addition to this instance, Solana goes on to detail a number of other alleged Kalshi related posts, included this since deleted gem from the account “Clown World.”

As of publication, this story has not been picked up by the national media, and by Mr. Solana’s own admission, there are some issues with the reporting. Mr. Solana details a number of conflicts of interest that he has, including that “Pirate Wires has a paid partnership with Polymarket”, that “Founders Fund, where [Mr. Solana works] separately from Pirate Wires, is invested in Polymarket”, and that “Keaton Inglis, a Kalshi employee and another subject of this piece, interviewed for a job at Pirate Wires.” Without any corroboration or any statement from any of the principles involved there is really no way to pass on the veracity of this reporting.

But it might be true, and that provides an interesting juncture to discuss the ongoing competition between United State’s regulated event contract marketplaces like Kalshi and offshore crypto-rails prediction markets like Polymarket.

It is easy to imagine how Kalshi could have some degree of animus towards Polymarket. An older company, Kalshi was formed in 2018 and spent several years (and, likely, tens of millions of dollars) with no operations or revenue, simply working on acquiring a coveted DCM registration from the CFTC. This process must have been a grueling and stressful gamble of years of team members lives, with no guarantee of success.

Then, against the odds, the gamble paid off. In 2020 the CFTC permitted Kalshi to register as a DCM and they were finally allowed to legally offer prediction market products to retail customers in the United States. At the time, there were only a handful of legal prediction markets, and those were largely operating under academic exceptions that limited their use as practical financial products. Kalshi changed that, and this, alone, was a massive victory. It was not, however, a guarantee of commercial success.

Around this same time, Mr. Coplan launched Polymarket and took a, uh, different approach. While it is unclear if Polymarket ever entered the DCM pipeline, it is clear that it did begin operations immediately, building a crypto architecture to automatically create robust prediction markets. While it is difficult to find historical data, it is clear that it found some traction immediately, because it was effectively shut down in 2022 by the CFTC order I wrote about here last week.

Of course, we all know the story from there. Polymarket moved its headquarters to Panama, geofenced the United States, and kept on cooking—eventually it became the largest prediction market in the world by a big margin. At the last measure I saw, it was more than ten times the size of Kalshi.

Meanwhile, DCM or not, it seems that Kalshi experienced somewhat slow adoption, likely having trading volumes in the low hundred millions in 2023. That’s pretty good, but it may not be enough to justify the enormous legal spend that went into forming a licensed entity. It was relatively easy to see why—political prediction markets are generally considered the most important and most popular by the industry, and while Polymarket listed whatever they wanted, the CFTC refused to allow Kalshi to list them. This was such a problem that, eventually, Kalshi was forced to sue the CFTC to attempt to list the contracts. To their eternal credit, they fought a gutsy court battle for a whole year to gain the right to list political contracts. Again, after likely spending millions of dollars in legal fees, Kalshi won in D.D.C. and won again in the D.C. Circuit. On October 8th of this year, finally, Kalshi listed “fully legal” political prediction markets.1

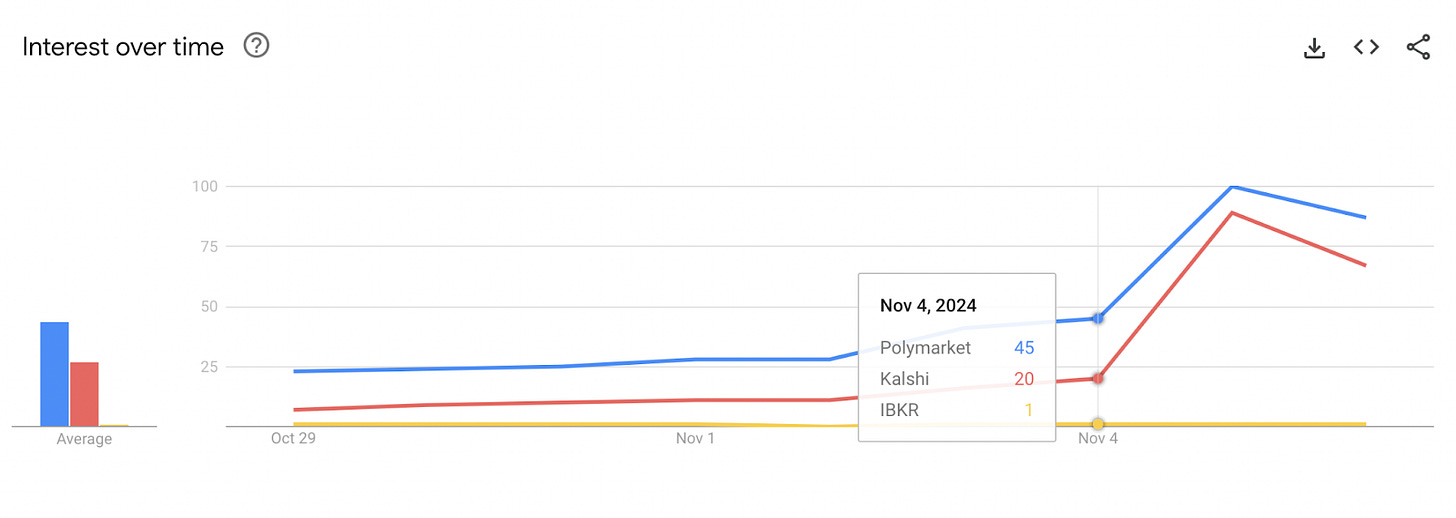

But when Kalshi arrived on this most lucrative scene, it found Polymarket already there. By the time Kalshi arrived, Polymarket had used its head start to build vast market share, global reach, and, meaningfully, at least twice the brand recognition of Kalshi. They were winning.

So it is easy to see how Kalshi and its principals might be cheesed off! You see the dynamic here right? Kalshi is the grinder who always plays by the rules, and Polymarket is the brilliant iconoclast carving their own path. And nobody, nobody, hates the rebel who flouts the rules more than the competitor who has made their way by adhereing to letter of the law.

Kalshi fought the battles, they carried water for the whole industry, and yet they still trail a marketplace that was operating outside of traditional legal norms. Yes, technically, Kalshi and Polymarket should have nearly completely distinct user bases, because Polymarket blocks individuals in the United States from accessing the platform, while Kalshi is only available to U.S. Persons. But there are anecdotal reports of U.S. traders using virtual private networks (VPNs) to access Polymarket anyway, and many think these markets are substantial. This would be very annoying, and I can see why, if you were Kalshi, you might want to draw attention to Polymarket’s arguably illegal operations.

If I was Kalshi’s lawyer, though2, I would advise my clients not to get involved in the sort of sharp elbowed tactics alleged in Mike Solana’s article. There are a number of legal and non-legal risks to this kind of action, and I generally think they predominate. Here’s why:

By paying influencers to smear Polymarket, you could expose yourself to direct legal liability. This kind of tactic, in general, could give rise to a number of legal claims, including defamation, Lanham Act unfair competition and false advertising, business disparagement or trade libel, or plain old defamation. In this case, most of these claims would probably not pertain, because the alleged Kalshi statements probably don’t appear to be strictly false. Antonio Brown’s statement is an opinion couched as an opinion, and while the Clown World post probably exceeds the facts by calling Polymarket an illegal betting scheme (the exact detail of any possible charges is unknown currently), it is basically characterizing the events accurately.3 In addition, with respect to unfair competition claims, I am not sure Polymarket would even have standing to sue under the Lanham Act since they are not legal market participants in the United States.

One cause of action that does seem plausible, though, is FTC consumer protection violations. Influencers posting on social media have a legal obligation to disclose when they are being compensated for the post. This obligation extends to the companies paying for the media, and the FTC has historically brought action against entities deceiving consumers in this way. While this would likely be a small matter dollar-wise for the FTC, the salacious nature of the story could draw enforcement anyway, and for a business like Kalshi, any enforcement could be a big problem for a second reason…

By drawing regulatory attention with this kind of smear campaign, you risk your license. Kalshi obtained a difficult to acquire DCM registration in 2020, and that legal status is the crux of their whole business. Making risky moves like a social media smear campaign could undermine the integrity of that registration. In this case, the magnifying glass is even more pronounced—Kalshi has been in contentious litigation with the CFTC for months over a subset of markets that it lists dealing with political outcomes. The CFTC has made no bones that it wants these down. Participating in anything that could be perceived as untoward could not only negatively affect the outcomes of that still pending litigation, it could potentially give the CFTC a vector of attack should they wish to shut down your project through other avenues.

Generally, DCMs must comply with certain “Core Principles” specified in 17 CFR Part 38, including in Subpart M the requirement that “a designated contract market must have and enforce rules that are designed to promote fair and equitable trading and to protect the market and market participants from abusive practices including fraudulent, noncompetitive or unfair actions, committed by any party.” While an FTC enforcement action may not trip this obligation, someone could probably argue that it does with a straight face. There will be other arguments as well, and when you rely on the discretion of an agency like the CFTC to keep breathing, you probably don’t want to show up in any negative headlines. When your whole business relies on permissive regulatory status, better not to test it.

Finally, by engaging in a sketchy smear campaign, you may risk harming your own reputation. I don’t know how many people give credence to Antonio Brown’s perspective on legal matters, but I would guess that he does not sway many crucial stakeholders. On the other hand, any practice that could reflect badly on your company risks being widely repeated on social and traditional media if revealed. For purely pragmatic reasons, then, the risk and reward calculus appears skewed against this kind of tactic in my mind.

As I have said repeatedly, we do not know whether the allegations in the Mike Solana piece are true or not. We may never know! Nonetheless, young companies reading this should consider their broader legal context, and the risks they would be absorbing, before they attack competitors. We all want to be Carl Icahn and Bill Ackman confronting our adversaries on CNBC, but my two cents: it's not worth it.

The Blockchain Association won in Texas

I’ve covered some Texas litigation here in the past—most notably Crypto.com’s SEC complaint—and basically my take is that if you gotta fight, that’s about as good a place as any to do it. Well, I feel awful vindicated this week after the Crypto Freedom Alliance of Texas and the Blockchain Association proved me right by winning a complete summary judgment victory over the SEC in N.D.Tex.

This ruling, handed down by Judge Reed O’Connor, actually involved two parallel cases simultaneously—Crypto Freedom Alliance of Texas v. SEC and National Association of Private Fund Managers v. SEC.4 These cases are the culimination of litigation arising from a final rule promulgated by the SEC in February of this year. That rule, referred to as the “dealer rule”, attempted to expand the subset of securities purchasers who would have to register as dealers.

This is actually really important, the historical criteria for who could be considered a dealer was fairly straightforward, encompassing “individuals or firms that, among other things, hold themselves out to customers as willing to buy and sell securities, using their own inventories to provide those customers with liquidity.” These dealers provide a number of services but, crucially, are in the business of setting prices by making markets, which means buying assets and maintaining inventory.

The dealer rule, as structured by the SEC in February, would have instead expanded the definition of dealer to anyone who “[e]ngages in a regular pattern of buying and selling securities that has the effect of providing liquidity to other market participants [including] by… [r]egularly expressing trading interest that is at or near the best available prices on both sides of the market for the same security, and that is communicated and represented in a way that makes it accessible to other market participants.” (emphasis added). Note that this is only a small difference in definition, but a large difference in obligation, because while the old rule applied to those purposefully participating in the business of securities dealing, the new definition could apply to anyone whose activities had the ex post effect of regularly providing liquidity, which it turns out probably includes both many hedge funds and DeFi liquidity pools too.

This, in turn, is extremely important for crypto specifically because being a dealer is quite costly. It comes with a number of ongoing compliance obligations including risk, capital, and recordkeeping requirements and mandatory registration with FINRA. Beyond compliance, you have to apply to be a dealer, and it is costly and time consuming to do so. More importantly, if you are a DeFi protocol that is, arguably, just a bunch of code on chain5 then you may not even be able to apply. If you do apply, your application may not be granted. It is also possible that individual liquidity providers to liquidity pools would themselves be required to register as dealers, which, given the diffuse nature and small individual contributions involved, would obviously be unworkable. All of this would be bad!

Of course, many crypto entities raised these issues with the SEC during the notice-and-comment period of rulemaking, but the SEC promulgated the final rule nonetheless. Indeed, the SEC only addressed the applicability at all by noting that the dealer rule would apply to “any digital asset that is a security or a government security within the meaning of the Exchange Act.” Not very helpful!

Well, it turned out that Judge O’Connor did not agree with the SEC’s approach here, as he ruled “that the Rule is in excess of the Commission’s authority based on the text, history, and structure of the Exchange Act.” Judge O’Connor went on the vacate the rule “[b]ecause the promulgation of the Final Rule was unauthorized, no part of it can stand.” To put this in laymans terms, the judge basically told the SEC to get bent.6

This was a complete victory for the plaintiffs, which is a little bit rare to get. I’ve only had a few total wins on dispositive motions over the years, and it is a really good feeling, so congratulations to all of the attorneys involved. Obviously, the SEC may want to appeal this ruling, but given the structure of the court system, they are unlikely to find a sympathetic panel on the way up. Just this year the Fifth Circuit overturned another case concerning SEC rulemaking brought by the National Association of Private Fund Managers, and the Supreme Court, for its part, seems intent on dismantling the administrative state in its entirety.

More than this, as I mentioned at top, the composition of the SEC is about to change. This kind of rule, which only passed 3-2 over Republican dissent, is likely to fall out of favor. In other words, there is much to celebrate here. The cryptocurrency industry may be getting a fair shake at last, so lets make the most of it.

I flattened a lot of the complexity of this case to fit it in the newsletter, so if you are interested, I suggest you check out Blockchain Association Policy Counsel Laura Sanders’ appearance on the Thinking Crypto podcast, where she addresses the case with much greater detail and lucidity than I could here:

As were its competitors like IBKR and Robinhood, who quickly spun up their own prediction markets

Which to be clear, I am not. Other than passing DMs I haven’t spoken to anyone involved in these stories and have no first person knowledge of the alleged events.

It might be a little mean to call Mr. Coplan an “SBF Lookalike”, but this is probably not actionable.

Which is a little disconcerting to read—flipping back and forth through two documents in two different cases—but do your thing Judge O’Connor.

Or if your legal argument to avoid other regulation depends on being a simple agglomeration of code without legal structure.

I think this is what Sarah Isgur refers to as “naw dog-ing.”

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.