DAO-n’t Even Think About It

Also, Pump.fun is still having a bad time and the SEC is still fighting Binance.

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with legal questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

Something that I’ve never written about here before, but which turns out to be quite important to the cryptocurrency industry as a whole, is that DAOs are bad. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) are an old crypto idea, possibly predating even the bitcoin whitepaper, whereby an organization's rules, rather than being a product of traditional corporate governance, are codified into smart contracts running on a blockchain. Through DAOs, actors can interact anonymously (or at least pseudonymously) to accomplish common goals.

Historically, a lot of crypto actors in the before-times of 2021 and earlier saw this as a protective step, whereby any regulatory or legal deficiencies of a firm's cutting-edge products are ameliorated because, well, nobody can find them and do anything about it. This coincided with a libertarian contractual conception of “law” where instead of having a centralized sovereign enforce legal and regulatory constraints on parties, the parties could theoretically define them for themselves, reach consensus, and live with the outcomes. In theory, if the underlying programmatic design is good enough this can foster as much (or more) trust than the government enforcement model.

There are a few problems with this view, though. For one, smart contracts aren’t so secure that they can implement a trusted environment to conduct permissionless business without government enforcement, and a lot of people have lost money, been scammed, and generally gotten screwed in DeFi. For another thing, governments don’t agree that the rules of computer code supplant actual law, which can create situations like the Mango Markets scammer Avraham Eisenberg, where an actor ostensibly follows the internal logic of some bolus of code, but still breaks the law while doing so. Third, people who lose their money know that the government feels this way, and, even if they buy into the “code is law” ethos prospectively, they will still appeal to government actors for help after an adverse event.

This reality coincides with two uncomfortable truths about DAOs as a structure. First, you’re not that anonymous. Private lawyers and blockchain investigators can probably find you, and the United States Government can definitely find you if it wants to, so the actual protection of anonymity should be discounted to zero. Second, and pertinent here, a DAO is a terrible structure for doing business.

Ok, for some history, the LLC is a modern invention—only originating in the United States in 1977. Corporate forms generally exist so that individuals can make big bets on business without accruing personal liability while doing it. If you went to debtors prison when your business failed, you would be less likely to start one, right? Before corporate forms became commonplace, business was often conducted through partnerships, and one defining feature of partnerships was joint and several liability. This term-of-art means that each partner is liable for the entirety of any liability of the partnership.

And, wow, this really sucks. If you have a lot of partners, then any of them could create some giant liability in the name of the business, and the victim can come after you for all of it. Technically you are not responsible for all of it, but the law doesn’t care, you pay the plaintiff everything and then you have to go try to collect from your partners. And good luck.

Understandably, this form is rarely used now. Even for businesses like consultancies and law firms that were traditionally structured as partnerships, limited liability partnership structures have been broadly adopted to protect against this terrible feature of traditional general partnerships. But the form still exists! Just sitting there in the common law. And the default is that if a group starts doing business and doesn’t create a corporate form, it is considered a general partnership.

You see where I’m going. All these DAOs with ostensibly no legal existence did in fact have a legal existence, it was a general partnership. That meant that every DAO member was maximally exposed to risk at all times. While this classification had been merely a theory for some time, it was first endorsed in the CFTC’s Ooki Dao case last year. Well, things just got worse for the DAO. On November 18, N.D. Cal. ruled in Samuels v. Lido DAO that Lido DAO is in fact a general partnership with the capacity to be sued. That’s bad news.

There is hope though. As I’ve written here before, Wyoming is pioneering legal structures to provide liability protections to DAOs, including the DAO LLC and DUNA. We will discuss these in more detail here in the future.

In the meantime, and none of this is legal advice, I really would think hard before I started a DAO with no corporate form.

I Was Right

Last week I wrote about Pump.fun’s un-fun content moderation issues. The platform has earned in excess of $285 million in revenue this year, and apparently put some of that into developing social features that would help users “pump” their tokens issued through the platform. One of these social features was live streams and, oh boy, people abused them.

Last week when we left off, Pump.fun was apparently taking responsible steps to remediate the damage. They first attempted moderation and shortly thereafter removed the livestream feature altogether. There hadn’t been any government response at the time, but I wrote that this kind of rapid expansion into hosting streams was risky for a number of reasons including:

Bad press, even for activities that are legal, is a major risk for businesses on otherwise unsure regulatory footing. Pump.fun is run by an anonymous founder and its corporate status is unclear, so it is difficult to evaluate its underlying regulatory risk. Nonetheless, it is easy to see how a platform like this could be used for money laundering, and I would be shocked if it never has been. This means, in effect, financial regulators could have plenary authority to investigate and press criminal charges whenever they choose (although this authority might be diminished by a ruling we will get to a little later). I’m not saying that this environment is fair, but that’s the reality. And if some poor teen kills themself on one of your livestreams, you can bet those regulators will take notice.

Luckily nobody hurt themselves on a Pump.fun stream (as far as I know), but that fact seems not to have saved the platform itself. In the wake of this unwanted publicity, the platform has apparently been banned in its home country, the United Kingdom. On Tuesday the UK Financial Conduct Authority published a warning noting: “This firm may be providing or promoting financial services or products without our permission. You should avoid dealing with this firm and beware of scams.”

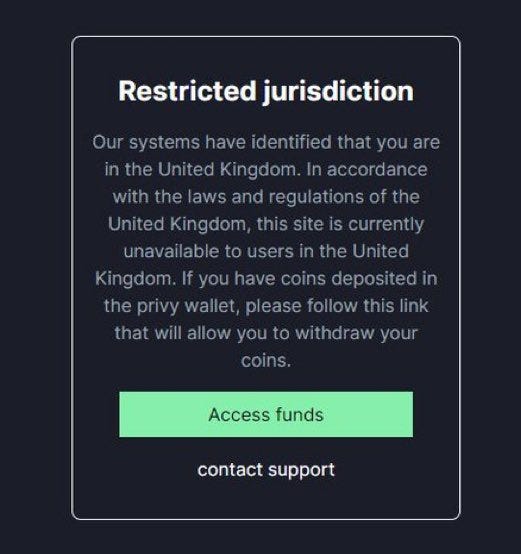

Shortly thereafter, UK users lost access to the platform and received the following notice while visiting the URL:

CoinTelegraph has reported that this is due to a “ban” in the UK. Exactly the kind of adverse event that I feared might follow negative publicity. Regulators, after all, are just people. When they see a firm that is arguably in their remit in the news, they start to feel pressure to do something about it. Maybe someone at a cocktail party mentions it, maybe a server at Nando’s asks why they aren’t doing anything. Either way, this kind of thing starts a clock ticking in the social environments and minds of people with the power to shut a project down, and that is a problem in our industry. You don’t really, meaningfully, have a right to do business anywhere—only permission—and with that mind, it is really better to stay under the radar until you can afford to pay lobbyists.1

While this is an obvious setback, and Pump.fun has reportedly experienced corresponding 66% decline in revenue, there are still relatively strong regulatory arguments in the United States for its operations. As a major star of DeFi in 2024, it seems plausible that the platform still has bright days ahead.

Now is the time for level-headed crisis management and hard work, and if all goes well, Pump.fun can push through. Still, it is better for any young firm not to face this kind of headwind, or at least to put it off as long as possible. The best way to do that is to make sure that some internal controls are established from the outset and that there is an opportunity for multiple voices to be heard before major new product features like livestreams launch. I am biased, but I think that calls for a lawyer.

The SEC Squirms

So for some context, a little while back SDNY Judge Analisa Torres ruled that certain of Ripple’s sales of XRP were not securities transactions. These “programmatic sales” as Judge Torres put it, were excluded because they were characteristically blind bid-ask transactions, and the buyers had no idea who they were buying from. Many in crypto hailed this, rightly, as a major win. But some were less enthusiastic because the reasoning was a little, say, singular, and they suspected the ruling wouldn’t hold up on appeal.

Well, the SEC definitely felt that way, and tried to raise the issue in an interlocutory appeal, but failed. So that case went on for some time, and eventually resolved modestly favorably for Ripple in a summary judgement ruling, and that ruling now being final, the SEC could finally appeal the former ruling, and so they did, and that appellate litigation is ongoing now.

Well, that is not the only litigation ongoing, and the SEC threw some serious shade on Judge Torres’ reasoning this week in a different case they are pursuing against Binance.

On Thursday, the SEC filed its opposition to Binance’s motion to dismiss in their ongoing litigation. While not expressly repudiating Judge Torres’ reasoning (except to say that they disagree), the motion does everything in its power to advance arguments against its substance. In the Binance motion the SEC lays into the Ripple reasoning, as well as the broader interpretations some have made of an earlier ruling in this same Binance case, in arguing that secondary market sales of BNB and ten other cryptocurrency tokens including SOL are “investment contracts.”

“Defendants’ multi-faceted purported legal requirement—that the investor (i) must know that (ii) her funds ‘flow into’ the hands of the issuer and (iii) expect that they will be used for the enterprise—does not appear in Howey. That Howey may have presented those facts does not create a legal requirement, any more than the existence in that case of contractual obligations created one. Thus, none of the cases applying Howey over nearly eighty years, including the dozens cited across hundreds of pages of briefing in this litigation, impose as a legal requirement that the investor must know her funds are flowing to be used by the issuer. To the contrary, Defendants’ line of demarcation drawn at resales is inconsistent with long-standing precedent and the Court’s holding that even for secondary market transactions ‘it is the economic reality of the particular transaction, based on the entire set of contracts, expectations, and understandings of the parties, that controls.’”

As a matter of law, the arguments advanced by Binance and the SEC at this stage appear to be a close issue to me. It has been very in vogue of late for practitioners to distinguish between securities writ large and investment contracts as a specific subset of securities, which must meet the Howey test at the point of sale. This means, some argue, that most secondary sales are actually not securities at all because the money from the same doesn’t go into a common enterprise, but rather to some unknown seller on the other side of a trade.

In Ripple, this was enough for Judge Torres to rule that even trades between Ripple and third parties, i.e. primary sales, were not security transactions because the buyers had no way of knowing that they were purchasing XRP from Ripple. The obvious inference of that reasoning was that secondary market sales almost certainly were not investment contracts, although Judge Torres expressly disclaimed this conclusion in a footnote and left it as an open question.

The same reasoning was later bolstered by a previous Binance ruling, where D.D.C. Judge Amy Berman Jackson wrote in a footnote that (with respect to secondary sales) “the SEC seemed to be speaking out of both sides of its mouth[,] it took pains to disavow any intention to argue that once the assets were sold as securities, they retained that character forever.” Strong language indeed.

Judge Berman Jackson went on that:

“Insisting that an asset that was the subject of an alleged investment contract is itself a ‘security’ as it moves forward in commerce and is bought and sold by private individuals on any number of exchanges, and is used in any number of ways over an indefinite period of time, marks a departure from the Howey framework that leaves the Court, the industry, and future buyers and sellers with no clear differentiating principle between tokens in the marketplace that are securities and tokens that aren't”

This is quite powerful, but, honestly, I do not know how this court will rule on the renewed motion to dismiss in Binance. The previous Binance ruling ultimately came down to defects in the SEC’s pleading, and that document has now been amended.

Nonetheless, the outcome could turn out to be hugely influential for the future of crypto enforcement. If the SEC loses, that is a rebuttal of its entire enforcement program. If it wins, it would be empowered, but that hypothetical ruling could also set up a circuit split as similar questions are at issue in the Crypto.com case in W.D.Tex. and the 2nd Cir. in the pending Ripple appeal. For non-lawyers, a circuit split is a (usually) necessary predicate to the Supreme Court granting certiorari and agreeing to hear a case. If differing approaches come before the Supreme Court in the coming years, it could be an epochal showdown for the legal status of the whole industry. And you gotta think that panel is sympathetic.

There’s a political angle here as well. Gary Gensler is out and Paul Atkins is in at the SEC. While it might take some time for the enforcement attorneys to turn over or be brought up to speed, it is conceivable that many of these litigations will be dropped. In the short term, obviously, this would be great for these crypto institutions burning big cash on legal services. But in the long term, would it be better to fight and win these battles to fully enshrine the industry's legal status? The exchanges could, after all, end up losing these cases too. I don’t know. In the end, it will be Mr. Atkins and the new SEC’s decision, not ours, but something to keep an eye on.

Two More Stories

There are two more major developments that I don’t have time to cover now but are worth including. First, the attorney Bill Hughes relayed that, despite losing the 2024 election, the Biden IRS is proceeding with rulemaking that would impose tax reporting duties on software developers of non-custodial software. The proposed rule is obviously an infeasible administrative burden for DeFi that would undermine the legality of the DEX model.2 This administrative practice is sometimes called “midnight rulemaking” and is both common and somewhat distasteful.

Second, Coinbase chief legal officer Paul Grewel has been leading a FOIA campaign to understand the internal basis for “Chokepoint 2.0”, and has uncovered voluminous letters from the FDIC to banks directing them not to do business with the crypto industry.

Both of these stories are very important, but as I am currently in an airport, there is no way I can cover them this week and still get the newsletter out on time. Let me know which you’d like to hear about next week and I’ll include them here!

Until then.

Or in Pump.fun’s case, have gotten around to hiring some.

Such that there is one.

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.