Pump.fun Is Not Having Fun, but the Fifth Circuit Rarely Disappoints

Risk is a mutable concept in the interregnum, but that doesn't mean you have to eat it on purpose. Also: Marc Andreessen calls out the CFPB (perhaps unfairly), and Antonio Brown speaks out.

I started Brogan Law to provide top quality legal services to individuals and entities with legal questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help my clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email aaron@broganlaw.xyz.

Pump.fun is not Having Fun

Regulation is tricky. One of the strongest criticisms of the draconian SEC regulatory regime of the past four years is that while it has stifled venture backed start-ups making good faith efforts to comply with law, it has allowed crypto’s worst impulses to thrive in the shadows.

The “investment contract” based Howey regime used to categorize cryptocurrency tokens as securities was not designed for cryptocurrency tokens—it was designed for investment products. It is relatively easy, therefore, for the SEC to convince a judge that a token issued to raise money by a legitimate project—with a team and a website—is a securities offering. On the other hand, a memecoin launched by, say, c0ckwarri0r69.eth, promising the buyer nothing, and with no underlying organization, website, or marketing presence, is almost certainly not an investment contract.

This is because a crucial component of the Howey tests is the “reasonable expectation of profits through the efforts of others” prong. If the tokens are simply minted in a discrete number and sold into the world, with no suggestion of profit and no underlying enterprise to speak of, then it is very difficult to imagine the “efforts of others” prong being satisfied. There are no efforts of others! It’s just a meaningless meme—oh ho ho.

I’ve oversimplified the analysis, but in broad strokes this is true. It is harder for the SEC to go after true nonsense than legitimate projects.

Pump.fun is a platform that emerged in January this year to take advantage of this apparent memecoin loophole. Legacy memecoins like DOGE, Shiba Inu, and Dog Wif Hat have achieved relatively high, stable, market caps, which likely made their creators fabulously wealthy with relatively minimal effort.1 It wasn’t no effort though, since historically one would have needed some minimal technical knowledge to successfully launch a token. Pump.fun changed that—on the website one could simply press a button titled [Start a New Coin] and be ushered to input a minimum of information and launch your very own Solana based cryptocurrency token:

This product is a genius collision of lottery (if your coin takes off, you could get rich!), shitposting (search “pepe” on the pump.fun board), and regulatory arbitrage—and it has quickly grown to nearly $100 million monthly revenue in less than a year. Inevitably, this has led copycats to tweak the formula and try to take market share. Great product, relatively straightforward to build, hard to preserve your moat.

In an apparent response to this phenomenon, Pump.fun has recently been testing new products to accompany the token launcher itself, and this week one of these went very, very wrong. In August, Pump.fun introduced live streams, presumably so proponents can help their tokens pump.

As it turns out, social media is a thornier business than token launching, as Pump.fun learned this week when a wave of shocking content from its live stream platform was revealed on social media. X users recounted children brandishing guns and making threats and parents abusing children, all in the name of increasing the market caps of their respective tokens.

To their credit, Pump.fun quickly responded by first attempting content moderation and then disabling live streaming altogether. Despite this, lawyers took to X to excoriate the young project:

This story is still developing, and it's too early (and pointless) to scold Pump.fun. As far as I can tell, nobody actually followed through with any of the horrific threats posted there, so maybe the platform was able to avoid disaster. But still, this strategic blunder was clearly quite risky in several distinct ways:

Developing a streaming platform involves significant inherent risk. Platforms in the United States are generally shielded from the misdeeds of their users by Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934 stating that "No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider." However, there are a number of exceptions to this like copyright law and child abuse that must be moderate by the platform. Without developing robust moderation, your previously fun token launcher may suddenly be a wellspring of civil and criminal liability. That moderation, in turn, could undermine your Section 230 protection, so this is an extremely challenging area of law to navigate, and a serious expansion of regulatory surface area for Pump.fun.

Social features undermine your core regulatory arguments. A big part of the value proposition of memecoin platforms like Pump.fun is that the tokens launched there are probably not securities, improving regulatory prognosis for them going forward. However, if the platform is also used as a promotion vehicle for those tokens, some of them may end up being considered securities after all. Some of the participants may develop enterprises and promise purchasers returns on those enterprises, and all the sudden effort of others is satisfied and they are breaking the law. This is a problem for the platform itself because if the underlying assets are investment contracts, then it could arguably be considered a broker under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, since “the activities indicative of being a broker are soliciting investors, participating in the securities business with some degree of regularity, and receiving transaction-based compensation.” If it was a broker, Pump.fun would be required to register as Broker-Dealer with FINRA, which it hasn’t done and possibly can’t do, and so all the sudden it could find itself breaking the law.

Bad press, even for activities that are legal, is a major risk for businesses on otherwise unsure regulatory footing. Pump.fun is run by an anonymous founder and its corporate status is unclear, so it is difficult to evaluate its underlying regulatory risk. Nonetheless, it is easy to see how a platform like this could be used for money laundering, and I would be shocked if it never has been. This means, in effect, financial regulators could have plenary authority to investigate and press criminal charges whenever they choose (although this authority might be diminished by a ruling we will get to a little later). I’m not saying that this environment is fair, but that’s the reality. And if some poor teen kills themself on one of your livestreams, you can bet those regulators will take notice.

Like I said, this is not to scold. Pump.fun reacted quickly, and nobody yet knows what the consequence of this will be. However, it is a lesson for other young companies.

On some level, adverse events like this were inevitable. Pump.fun experienced massive success extremely quickly, and is likely flush with cash. At the same time, its founders probably see competitor projects taking market share and subjectively feel like the walls are closing in. This project likely felt enormous pressure to develop competitive services to maintain its sector lead, as does every company in its position. There was very little chance, given the time frame, that it could have the internal processes and controls in place in its first year of growth to manage those intense forces without some major adverse event occurring.

There’s no way to avoid that, it’s simply the pitfall of success, but what projects can do is talk to a lawyer early to make sure they have as much structure as possible early so that, when success comes, they are as protected as possible. An outside voice can be an invaluable check on unknown unknowns which could, ultimately, kill your business.

The Fifth Circuit Strikes Again

If you were on crypto legal Twitter this week, you became suddenly and forcefully aware of an ongoing litigation between OFAC and certain Tornado Cash users. This case has been percolating for a while, and this week Fifth Circuit Judge Don R. Willett dropped a bombshell opinion in favor of the Tornado Cash users. The community approval was explosive.

We talked about OFAC here a few weeks ago while discussing Tether. In this case, OFAC added “Tornado Cash to the list of Specially Designated National and Blocked Persons (SDN), [and] imposed an across-the-board prohibition against any dealings with Tornado Cash ‘property,’ which OFAC defined to include open-source computer code known as ‘smart contracts.’” Circuit Judge Willett admitted that the basis for this is sound, since these contracts were used by “a North Korea-linked hacking group that used Tornado Cash to launder the proceeds of cybercrimes.”

As a result of the block, certain bona-fide users lost legal access to the Tornado Cash smart contracts and, with the support of certain backers in the community, sued OFAC, arguing that it exceeded its statutory authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) by blocking “immutable” smart contracts. After losing in W.D.Tex., plaintiffs appealed and found a sympathetic panel in the Fifth Circuit.

The opinion turns on the statutory definition of “property”—under IEEPA, “the President is permitted to ‘block . . . any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest[]’” (emphasis added). Circuit Judge Willett does a focused investigation on the meaning of “property”, which he defines as “everything which is or may be the subject of ownership, whether a legal ownership, or whether beneficial, or a private ownership.” The Circuit Judge ultimately finds that “the immutable smart contracts at issue in this appeal are not property because they are not capable of being owned.”

Circuit Judge Willett attributes this peculiar feature of being impervious to ownership to the “immutability” of the relevant smart contracts. Tornado Cash performed a ceremony wherein they removed their right to edit or control the smart contracts, and so they no longer had a right or ability to modify them. This, to Circuit Judge Willett, means that Tornado Cash “does not—and cannot— own or control them[]”, which, in turn means that under “OFAC’s regulatory definitions, the immutable smart contracts are not property because they are not ownable, not contracts, and not services.” If they’re not property, OFAC cannot block them.

This is a monumental decision for crypto if it holds across contexts. It would mean, in effect, that a project can divest itself of liability for its work by structuring its smart contracts as “immutable.” It is hard to imagine that a court which finds that immutable contracts cannot be blocked by OFAC would find that software developer of contracts comprising a DEX, for example, would be subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) as a money transmitter, or that immutable perpetual future smart contracts are “contracts” within the meaning of the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA). Obviously, these contexts are different, and so the law may be interpreted differently, but, nonetheless, the implied standard is a gamechanger for the industry if it stands.

Whether it will stand, however, I am not sure. Some well known attorneys have suggested that they believe the Supreme Court is unlikely to reverse. After all, the current Supreme Court is quite skeptical of agency authority in general, and this is one of the very first cases to interpret agency authority narrowly under Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo. Still, I find the reasoning here disquieting.

Circuit Judge Willett is unfortunately strictly wrong in his critical analysis that the smart contracts at issue are not “subject to ownership” because they are “immutable.” The smart contracts run on the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), so while Tornado Cash does not have the ability to modify these contracts, it is nonetheless possible to modify the EVM itself to make the contracts “mutable” through a hard fork.

I am sure that the plaintiffs, and maybe Circuit Judge Willett’s clerks, presented the idea that it is impossible to modify the contracts, but to me, the adoption of that proposition in law is a step too credulous. Obviously, a hard fork would be incredibly difficult, requiring 51% of all ETH to agree, but “incredibly difficult” is qualitatively different than “impossible.”2 These smart contracts clearly could be subject to control and thus “property” within Circuit Judge Willett’s scheme, it is just unlikely that that will ever happen. This, to me, suggests that the “ceremony” performed by Tornado Cash either transferred ownership interest to the Ethereum network or abandoned the property, but did not magically transmute property into non-property.

Perhaps there is some threshold of decentralization after which property ceases to be subject to U.S. law, but the binary suggested by Circuit Judge Willett is a factual fiction. Whether the Supreme Court will care, I have no idea—but I would not take this judgement as an epochal victory just yet.

Kalshi’s (Alleged) Smears are (Seemingly) Confirmed

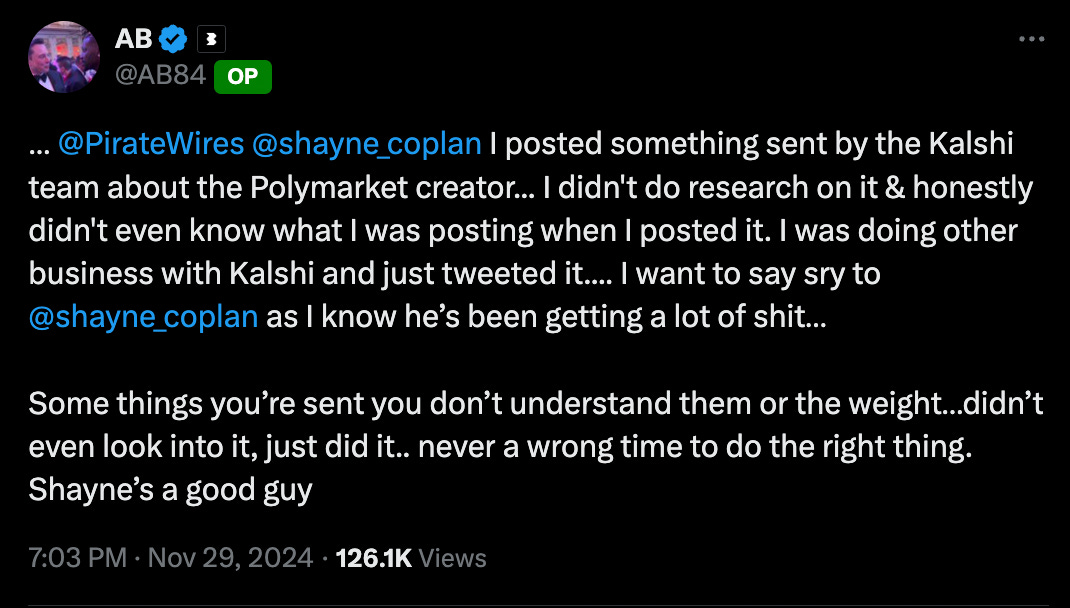

Last week we talked about the alleged smear campaign run by Kalshi against Polymarket. CoinDesk has since reported that there may have been a retributive campaign running the other direction, making the situation even messier. While the facts remain unknown, this week Antonio Brown seemingly confirmed the veracity of Pirate Wires’ reporting on X—stating that Kalshi asked him to post the smear and apologizing to Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan. Sad times for prediction markets.

Marc Andreessen Talked De-banking

On Tuesday, famed browser inventor and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen appeared on The Joe Rogan Experience to discuss the recent election. The conversation was far reaching, but one nugget gripped the internet's attention. Mr. Andreessen was discussing actions that the Biden administration took against disfavored industries and posited that the CFPB had driven a wave of “de-bankings” of cryptocurrency and fintech founders. Mysteriously, individuals whose income is derived from cryptocurrency often lost access to banking services during the Biden administration. Mr. Andreessen posited that this was part of a concerted effort by members of the Biden administration that he called Operation Choke Point 2.0.

Anecdotally, as many industry participants have said on X already, I have known clients to lose banking services, and it has long been extremely difficult for cryptocurrency companies to open bank accounts to begin with. Not to put too fine a point on it but this is a bad policy that should be remediated. Whether it is a government conspiracy, I have no idea.

It is worth noting, though, that some reporting has contradicted the CFPB’s alleged role in this scheme, and suggested that that agency, at least, is pushing back against de-banking.

This is obviously a meaty topic, and a fulsome discussion of this issue will take up more space than we have this week, so it will have to wait. Until then, you can always acquire bespoke legal advice by contacting Brogan Law!

Until next week.

I’m just guessing here as I don’t know for sure, and I suspect the creators of DOGE would not agree that it was a minimal effort. Still, it is fundamentally easier to make slop than it is to create a valuable enterprise.

ETH has a market cap around $500 billion, and Elon Musk has a net worth of greater than $300 billion, so in theory some (admittedly implausible) financial engineering could lead to a single person having control over the entire Ethereum network.

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisers.