Non-Newtonian Liquidity in Treasury Markets

Plus: will the GENIUS Act make it impossible to administer bankruptcy proceedings?

Brogan Law provides top-quality legal services to individuals and entities with questions related to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency law is still new, and our clients recognize the value of a nimble and energetic law firm that shares their startup mentality. To help our clients maintain a strong strategic posture, this newsletter discusses topics in law that are relevant to the cryptocurrency industry. While this letter touches on legal issues, nothing here is legal advice. For any inquiries email info@broganlaw.xyz

We are entering crunch time in the GENIUS Act saga. According to my sources, work on the bill is likely to be completed before the July 4th Congressional recess. Last week, I talked a little bit about the macro environment nudging U.S. sovereign debt rates up over the long term, and suggested that might be good for issuers like Circle.

This week, I want to return to the relationship between stablecoins and the Treasury market with a discussion of Vanderbilt law professor Yesha Yadav and former Fed economist Brendan Malone’s recent draft paper fittingly titled “Stablecoins and the US Treasury Market,” which explores the systemic vulnerability that this collateral model might introduce.

If you have read my various explorations of the relationship between the stablecoin market and the broader financial system, I highly recommend you check out the paper. I’ve attached the PDF here:

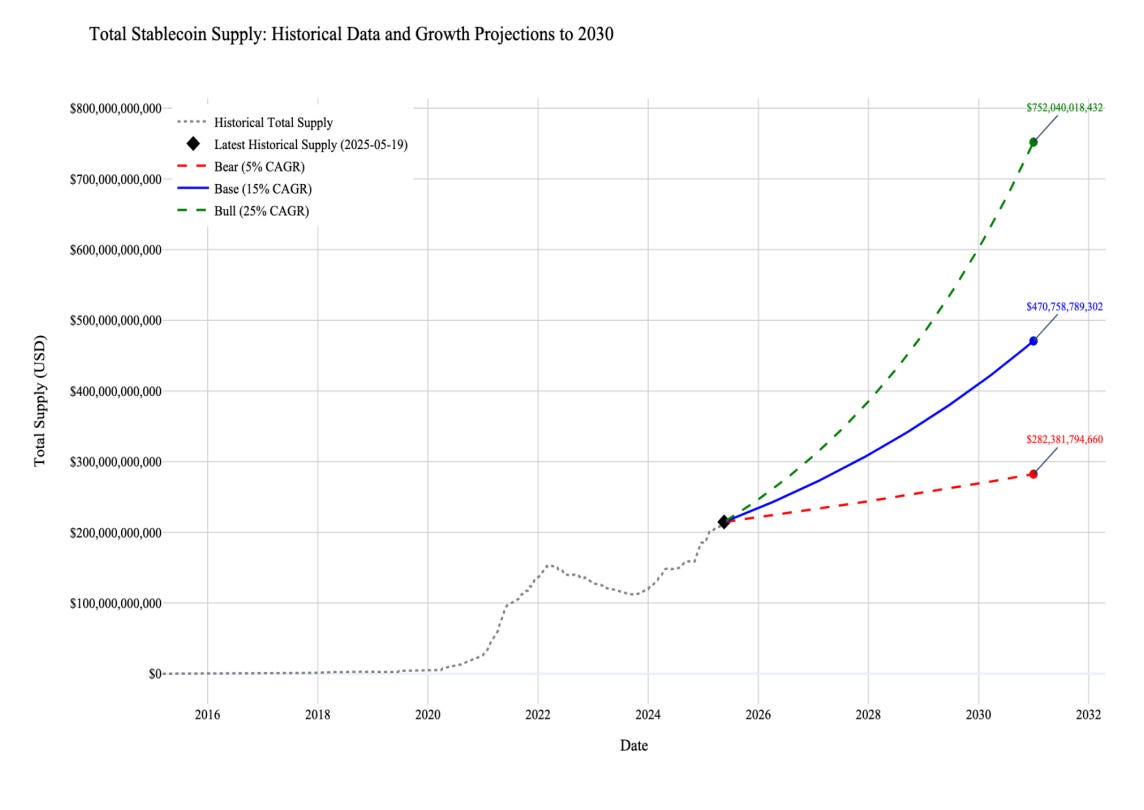

Prof. Yadav and Malone’s central thesis is that the dynamics underlying the stablecoin collateral model may not be scalable because of limitations in the Treasury market. USDC currently has ~$60 billion circulating supply, and matching collateral mostly held in Treasury bills with relatively short maturity. This is relatively small compared to the ~$900 billion in daily secondary trading of Treasuries, and so we can be relatively confident that, if Circle has to liquidate assets1, there would be counterparties available. If, however, the stablecoin market continues to grow, as current projections expect, this assumption is unlikely to hold.

Historically, United States Treasury debt has been treated as a “risk-free asset” and safe haven during instability, which had driven down yields in the crisis. For example, Prof. Yadav and Malone point to rates touching 0% in 2008 as the paradigm of this phenomenon.

This, obviously, is very good for the United States because it allows it to borrow money cheaply in times of turmoil and then tactically use that money to address the crises. As I pointed out here last week, however, long-term increases in the U.S. debt burden strain this system, and it is not clear that the U.S. Treasury market would function the same way it did during the 2008 Financial Crisis today.

Since 2008, the total volume of outstanding tradable Treasury debt has increased dramatically, rising from $4.8T in August 2008 to $28.6T in March 2025. This scale alone means that it will be more difficult for markets to absorb sudden, large-scale movements in this debt. There just aren’t big enough pools of capital sitting around to buy it!

This is compounded, in the authors’ view, by the greater post-2008 regulatory burden that banks face in absorbing new assets onto their balance sheets.

[P]rimary dealer banks have raised concerns about tightening space on their balance sheets, limiting capacity to reliably deliver liquidity. Regulatory requirements on banks to maintain deeper rainy-day buffers of capital – a function of post-2008 attempts to bolster bank safety – are often cited as having unintentionally made it costlier for banks to provide liquidity. That is, buying new Treasuries means setting aside sufficient capital reserves to mitigate a primary dealer’s increased systemic prominence within the financial system. As such, facing both competitive pressure from high-speed securities firms alongside a tougher compliance climate, primary dealers confront powerful incentives to avoid fully participating in Treasuries trading and liquidity production.

Warning Signs Have Already Emerged

Oobleck is a substance made by mixing two parts cornstarch with one part water. Known as a “non-Newtonian fluid,” it has the curious property of behaving like normal liquids most of the time, but suddenly behaving like very robust solids under pressure.

According to Prof. Yadav and Malone, there is some indication that Treasury markets may now behave similarly, appearing liquid in normal conditions but suddenly hardening during crisis. The authors point out that this occurred in both (i) March 2020 when, during the COVID-19 panic, “[i]nvestors could not find a counterparty with which to trade their Treasuries, causing prices to become deeply distorted,” and (ii) April 2025 during the Trump tariff crisis when “Treasuries trading experienced severe illiquidity and unusual price movements.”

The authors argue that this dynamic, combined with the likely increased size of the stablecoin industry, creates systemic risk to both the U.S. Treasury market and the stablecoin market.

For stablecoins, it's obvious why. Imagine Circle builds a $500 billion pile of short-dated Treasuries, and then experiences some “negative exogenous shock” like a cyber incident.2 This event, independent of the quality of their collateral reserves, could nonetheless trigger redemption action, which would accelerate if there was a hint of illiquidity in the Treasury market. If, in this scenario, counterparties were not available at Circle’s marked-to-book prices, it could quickly become insolvent.

On the other side, though, such an event could also undermine confidence in Treasury markets. The authors note that “growth of the stablecoin industry appears to be taking place without significant regard for the capacity of the Treasury market to sustain this growth in practical terms” and “U.S. Treasury markets will need to be available both to a growing stablecoin sector as well as to the usual borrowers that are using Treasuries as part of their own investment strategies.” As the demands of stablecoin issuers grow, they might crowd out other buyers of U.S. Treasury debt, pushing these erstwhile purchasers to different assets and leaving a less robust set of buyers behind.

This dynamic could also distort U.S. fiscal policy. The authors point out that Treasury debt is traditionally composed of only ~20% short-term obligations. This is good, because selling longer-term debt like 30-year Treasury bonds “means that policymakers can typically plan out various initiatives that require decades-long spending.” If the mix becomes relatively weighted to short-term instruments, the government will be left exposed to rate fluctuations, and so “regulatory objectives for stablecoins may well shape how the U.S. government funds itself and the costs that it has to pay to do so.”

What’s Really Happening Here

The degree to which the drafters of GENIUS have thought through these risks is hard to say. The need to establish buyers of U.S. debt is widely understood in Washington, and key sponsors of the bill, Sens. Hagerty, Gillibrand, and Lummis have all made public statements about its power to preserve “dollar dominance”

But what is this bill really establishing? By legally sanctioning, and restricting, the stablecoin industry, GENIUS is effectively creating something akin to a privately administered U.S. dollar purchasing portal.

In effect, GENIUS deputizes stablecoin issuers as wholesale buyers of U.S. debt. The 1-1 collateral rule funnels new token revenue into Treasury bills, and the net yield the issuer pockets is, in practice, a fee Washington pays for that captive demand.

Currently this market is still relatively small. But if it does scale to $2 trillion, stablecoin holdings would approach 40% of all outstanding short-dated Treasury bills, representing the government’s largest creditor and a run risk that will be impossible to ignore.

Despite the gripes I have had about GENIUS at various times, there is nothing inherently wrong with this bargain. It serves a purpose for the government, probably keeps rates down domestically, and also generates a product that is useful. Win-win-win.

But we should be clear-eyed about what is coming. The United States is not going to absorb greatly increased monetary risk without exercising control over its domestic counterparties. What looks benign at ~$200 billion market size is going to look like a ticking time bomb at $2 trillion and, in the long term, we shouldn’t assume that stablecoin adoption will end there. With M2 (money supply) approaching $24 trillion, it is plausible that stablecoins could far exceed $2 trillion.

At that stage, for all the reasons Prof. Yadav and Malone identified, it might be implausible for private markets to provide emergency liquidity in a run. And this, in turn, increases the risk of a run! If the vulnerability of a future stablecoin market becomes widely known, it could destabilize stablecoin markets as even minor shocks could provoke capital flight.

Is it likely that the government will let the largest purchaser of its debt become insolvent in this situation, or will it backstop the industry? I hope this question reads as rhetorical to you. And as it turns out, when the government starts to think it will have the responsibility of insuring an industry, it starts to become very interested in the details of that industry’s operation.

Prof. Yadav and Malone conclude with three policy insights. These are, first, that “regulatory coordination is necessary between those overseeing the Treasury market as well as policymakers in charge of stablecoins,” second, that policymakers should ensure that “market making practices in the secondary market for Treasuries are strong enough to manage the increased demand from stablecoin issuers,” and, third, that “the deeper interconnection between Treasury markets and the stablecoin industry means that digital asset technology is bridging two of the US's most important institutions: dollar payment systems and the country’s creditworthiness.”

And indeed, it is essential that policymakers are prepared to marshal their tools when the time comes. But the industry should be ready too, because if the GENIUS bargain goes through, they are likely to be regulated much more like banks are today.

In conversation, Prof. Yadav told me “I don't think that the GENIUS Act is the last word on stablecoin regulation. It's a framework to begin the process of including stablecoins within the regulatory perimeter and putting some basic measures in place to create a supervisory and permission structure for stablecoins to be issued and their risks managed federally. There are still going to be some pretty significant structural issues that will need to be carefully resolved in subsequent legislation or rulemaking that speak to safety and soundness concerns for the overall scalability of stablecoins.”

Buckle up.

Some Bankruptcy Considerations

[6/16/2025 NOTE: One reader pointed out that the function of the bankruptcy priority provisions described below have been changed in the updated Hagerty-Gillibrand ANS version of GENIUS. We’ll address this update next week. The new language addresses the concerns at the margin, but does not change the core issue described below, so I am leaving this as is for now. Just note that the language has since changed.]

Bankruptcy is great. In the old days, if you ran out of money to pay your debts, they locked you in the stockades and threw eggs at you. As a consequence, people were pretty nervous about taking on debt to do things.

But debt is also great. You have an idea that will make lots of money in the future, but you need money to get started. Without lending, you’re out of luck and have to return to the salt mines. But with credit, you can leave the mines, pay for your new idea, enrich society with the automatic salt miner you developed, and then pay your creditor back with interest. Everyone wins.3

So our enterprising founders included Article I, Section 8, Clause 4 (part 2) in the Constitution, which says that Congress shall have the power to establish “uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States.” And then Congress established (and periodically updates) the Bankruptcy Code to allow this to happen.

Now, the way this works is quite complicated, which is why Ray Schrock has so many homes.4 But at a high level, the first thing filing bankruptcy does is impose an “automatic stay” on all creditor claims to pause recovery against the debtor’s estate.

The code then creates a “waterfall,” which determines the order that the creditors get paid. Which goes something like (1) first lien secured creditors … (last) common stockholders.

Which is great, without the automatic stay, debtor assets would be first-come, first-serve, and it would be impossible to reorganize. Without the waterfall, it would be impossible for creditors to appropriately underwrite risk, making efficient lending markets impossible.

And all this runs great, except you also need lawyers and other professionals to do work to effectuate the bankruptcy proceedings, and the payment terms of a bankrupt debtor are uncertain by definition, so professionals might hesitate to undertake that work.

To remedy this, the Code puts professionals above the waterfall, which leads to the lawyers almost always getting paid first.

Well, some are speculating that GENIUS would change this, and that could be a big problem.

The provision at issue is Sec. 9 of GENIUS, dealing with the “Treatment of Insolvent Payment Stablecoin Issuers.” It states, “the claim of a person holding payment stablecoins issued by the payment stablecoin issuer shall have priority over all other claims against the payment stablecoin issuer.”

This language is certainly not artful, and if it does result in stablecoin holders gaining first priority in bankruptcy, it might complicate lawyer compensation.

As a gating issue, I should note that I don’t think it is certain that this language makes it into law. Unlike the structural changes to the bill that I have sometimes raised, which I don’t think are possible to remedy at this stage, this Sec. 9 language does seem like the kind of thing that could plausibly change in amendments to the bill, such that there are more in the future.

But in any case, I don’t clock it as certain that Sec. 9 will place stablecoin repayment above professional compensation on the waterfall. Yes, a textualist reading of Sec. 9(b), which inserts language into 11 U.S. Code § 507, is unambiguous. “Notwithstanding subsection (a), any claim of a person holding payment stablecoins… issued by a debtor shall have first priority over any other claim against the debtor under this title.” Administrative expenses, allowed under 11 U.S. Code § 503, are certainly “claims” as defined by 11 USC 101(5), and so it is difficult, from this frame, to imagine a way out.

But courts do not always interpret law from a textualist perspective. In this case, the interpretation of the law that would prevent payment of professionals would be so distortionary to bankruptcy practice that I still think it is likely that bankruptcy judges will fight tooth and nail against it. How exactly is beyond the scope of this newsletter, but perhaps they would use other provisions of the Code to route payment, use the mechanism of segregating stablecoin claims as “held in trust,” or other techniques.

That is not to say that, in a Loper-Bright world, these tactics would ultimately prevail. Appellate courts might overturn the rulings of bankruptcy judges. But even there, I think the likelihood that practicality will ultimately rule in this case is relatively high. If you think this country’s highest courts always make internally consistent decisions, read the order in Trump v. Wilcox and get back to me. There is still discretion in the system, and it could be used here.

This is a hard issue and I would love to hear your thoughts on it. I think it remains an open question going forward just what would happen if a GENIUS stablecoin issuer popped.

Thanks to the inimitable Will White for bringing this issue to my attention.

Until next week.

Brogan Law is a registered law firm in New York. Its address and contact information can be found at https://broganlaw.xyz/

Brogan Law provides this information as a service to clients and other friends for educational purposes only. It should not be construed or relied on as legal advice or to create a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking advice from professional advisors.

As Prof. Yadav and Malone point out, Circle did exactly this in March 2023 when its banking partner, Silicon Valley Bank, was distressed.

Credit to Prof. Yadav for suggesting this example to me.

Just don’t tell the Teamsters.

To be clear, this is a joke. I have no idea if Ray Schrock indeed has multiple homes. But, safe to say, bankruptcy lawyers do well.